Setting Boundaries with Clients

📚 This is Blog #5 in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series (Click to explore the series)

Weekly honest support for the struggles every clinician faces: “I hate group therapy.” “I can’t do this.” “My client hates me.” “I’m making it worse.” “I can’t say no.”

These aren’t signs you’re failing. They’re signs you’re human.

It’s 1 AM and I’m still in the office.

Not because I had a crisis. Not because someone was in danger. Because I scheduled clients for every single hour I worked, hoping someone would cancel so I could catch up on documentation. They didn’t cancel. They showed up. Because I had good relationships with them.

So now I’m exhausted, my fibromyalgia is flaring, the chronic fatigue is almost unbearable, and I’m the only person left in the building. I’ll set the alarm myself. Walk to my car alone in the empty parking lot. Drive home at 2 AM while my family sleeps.

And tomorrow I’ll do it again.

Not because I couldn’t say no. Because the work needed doing, and I knew how to do it. Because I had the energy and the systems and, honestly, the ego—I was good at this work, and I knew it.

I could see exactly what would happen if I said no: that client wouldn’t get scheduled. That group wouldn’t run. That court letter wouldn’t get written. And I had the skills to prevent that gap.

So I didn’t say no.

The problem wasn’t that I couldn’t set boundaries. The problem was that saying no had real consequences for real people—and I could see those consequences clearly enough that I chose to absorb them myself.

When “Yes” Backfires

A family asked me to write a letter for court. They needed it overnight.

I should have said: “That’s too soon. I need time to write something thorough and helpful. I can get it to you by [reasonable deadline].”

But I’m a people pleaser. So instead, I said yes. And then I didn’t get it done in time.

The family was angry. They complained. And suddenly I wasn’t the helpful, accommodating counselor who went above and beyond—I was the counselor who made promises she couldn’t keep.

That’s the thing about saying yes when you mean no: you think you’re being helpful. You think you’re showing dedication. But when you inevitably can’t deliver, you’ve done more damage than if you’d just set a realistic boundary from the start.

As we talked about in “I’m Making It Worse,” sometimes our attempts to be helpful actually cause harm. And sometimes that harm comes from saying yes when we should have said no.

What I Actually Regret (And What I Don’t)

I don’t actually regret working that hard.

I regret missing time with my kids. That part I’d change. But the work itself? The hours, the effort, the showing up when other people didn’t? I was young. I had the energy to take it that step further. I wouldn’t be able to do it now, but back then I could.

And honestly? I think if everyone could put some time in and give 110 percent, that would be great. We can’t all do it. We can’t all do it for long. But sporadically? That extra effort matters.

So this isn’t going to be a blog post telling you you’re doing too much and judging you for working hard. I would never do that. If you want to work as hard as I did, I’d share insights about how to do it efficiently, how to build systems that prevent mishaps, how to sustain it longer than you think you can.

My issue isn’t with counselors who work hard. My issue is with the systemic failure that REQUIRES us to work this hard just to support our communities.

I blame the agencies. The funding structures. The communities and society that underfund behavioral health and then act surprised when we can’t keep up. I judge them for creating conditions where we HAVE to work like this.

But I won’t judge you for choosing to do it anyway.

If you’ve ever worked yourself into the ground because setting boundaries with clients feels selfish, impossible, or like you’re failing everyone who needs you—this post is for you. Just like struggling to facilitate group therapy or questioning whether you can even do this work, difficulty with boundaries is something nobody prepared you for.

This Struggle Is Universal

Every counselor in their first two years faces some version of this: saying yes when they mean no, overcommitting out of guilt, and wondering why boundaries feel impossible.

That’s why the New Clinician Survival Kit Series exists—to normalize these struggles and give you practical tools, not platitudes.

Setting Boundaries with Clients: What It Actually Looked Like

I worked two jobs. 80+ hours a week. But it wasn’t like I was giving one job 60+ hours—I was splitting it, giving both jobs 50+ each. So people commented on my work performance, sure, but nobody was really bothered because I wasn’t always at one place. It didn’t look as shocking from the outside.

My supervisor gave me and my colleague a lot of leeway. We got the job done, maintained our duties, they didn’t ask questions. I wasn’t making mistakes, so they didn’t micromanage my schedule.

From their perspective, everything was fine.

From my body’s perspective? Not so much.

After 20+ days without a break, I’d cry from exhaustion—not because I was emotionally fragile, but because I’d been operating at maximum capacity and my body was giving me accurate feedback about sustainability. I would go a month or two without a day off. That was very difficult.

But at 1 AM when I was still in the office? I wasn’t angry. I was determined. Exhausted, yes. In pain mentally from pushing myself so hard, yes. The fatigue and joint ache from fibromyalgia—that was real.

But I also felt satisfaction. My system worked. I was very efficient, and so many things would get crossed off my list pretty quickly. That was rewarding. Motivating, even.

The problem wasn’t the late nights themselves. The problem was what I was missing while I was there.

The Real Cost of Not Setting Boundaries with Clients

My daughter was born and two months later I started working two jobs—80+ hours a week. I told myself it was for my family.

And it was. But there was a cost I didn’t see coming.

Early on, at a party, my daughter wouldn’t come to me. Wouldn’t come to anyone else either. Only her daddy. I spent the party outside, trying to distract myself, trying not to think about how I wished I was the only person she wanted—even though I knew that wouldn’t be fun either.

It was weird telling people “she’s with her dad” when they asked where she was. Explaining that she wouldn’t come to me. Her mom.

She would cry for her daddy when she was with me.

I knew it was because of my schedule. I knew it was because I was working for our family. But that knowledge didn’t make it hurt less when I missed milestones, when she reached for someone else, when I realized she was closer to him than to me.

That’s the part I regret. Not the work. The missing her.

Why Setting Boundaries with Clients Feels Impossible

Why “Just Say No” Doesn’t Work

People talk about setting boundaries like it’s a simple decision. Like you just decide “I’m going to say no” and then you do it.

But it’s not that simple when there are two voices in your head and one of them keeps winning.

I would hear it: You shouldn’t be doing this. Remember, you need good boundaries with work and with clients. You can’t work harder than them. You’re only one person.

And then the other voice would answer:

- But I’m literally the only person willing to take this case.

- But I have the skills to make this work.

- But this client will be excluded from this experience if I don’t.

That second voice won most of the time—not because of guilt, but because I was making a clinical assessment about what was needed and whether I could provide it.

I would take high-risk clients on community outings—clients with complex histories who needed structured community integration but who other staff had written off as “too difficult” or “not worth the risk.”

I did it because I knew how to manage those situations. I had the skills. I could read their cues, de-escalate before things went sideways, and give them access to normal experiences they’d been excluded from for years.

Other staff weren’t doing these transports. Not because they were setting healthy boundaries—because they didn’t want to deal with the complexity. They’d rather those clients just… not participate.

That felt exclusionary to me. These were people who already got left out of everything. Who got labeled “too much” everywhere they went. And yes, it required more attention. More clinical skill. More energy.

But I was good at it. And I wanted them to have those experiences.

The problem wasn’t that I took on complex cases. The problem was that I was one of the only people willing to, and the system knew it—and took advantage of it.

That’s what nobody talks about when they tell you to “set better boundaries.” They’re not asking you to protect yourself. They’re asking you to stop filling gaps the system should be filling.

The Boundaries I Could Hold (And the Ones I Couldn’t)

The Professional Boundaries Were Easy

Here’s what’s strange: I was GOOD at setting many boundaries.

When clients pushed for friendship instead of therapy—when they wanted my personal cell phone number, tried to add me on social media, asked invasive questions about my personal life, initiated touch or intimate moments—I held that boundary well.

“This is necessary for you and I,” I would say. And I meant it.

Those boundaries felt clear. Professional. Easy to defend. Research on professional boundaries in therapy emphasizes that these clear professional limits are actually easier to maintain than the subtle, everyday boundary decisions that wear us down over time.

The Money Thing Was Different

I would buy supplies for groups myself—activities, crafts, engagement tools. I knew it wasn’t technically my job, but I also knew these clients had been through dozens of cookie-cutter groups with worksheets and lectures. They were bored. Disengaged.

I wanted to create groups that actually worked. That kept people interested. That gave them hands-on activities while we talked—diamond dots, color by number, puzzles, bullet journals—so their hands were busy while their minds processed.

Other clinicians might not have done that, but they also weren’t running the volume of groups I was. And their groups? Attendance was spotty. Mine had waitlists.

Some clients knew I was paying for it myself. Others were very surprised when they found out.

“Why would you spend your own money on us?”

I didn’t talk about it much. To me, these experiences were often the first for them. I wanted them to have that.

And I don’t regret that either.

But I also can’t pretend I had unlimited resources. I didn’t have much money at the time. And every dollar I spent on group supplies was a dollar I couldn’t spend somewhere else.

This is expected when they tell you to “go above and beyond.” In teaching, counseling, case management, and more.

Why Setting Boundaries with Clients Is Harder in Addiction Counseling

It’s not just you. Saying no in addiction and mental health work is objectively harder than in other fields, and it’s not because you’re weak or have bad boundaries.

It’s because the work itself is designed in a way that makes “no” feel impossible.

The Reality of Client Need

Your clients aren’t calling because they’re bored. They’re calling because they’re in crisis, actively using, just lost housing, just got arrested. And you know—because they’ve told you—that you’re the only person they’ve talked to in three days who didn’t judge them or tell them to figure it out themselves.

That knowledge sits heavy when you’re trying to say no.

Their stories are genuinely heartbreaking. When someone tells you about being sexually assaulted at 12 and self-medicating ever since, when they’re asking for one more session this week because their mom just died and they don’t have anyone else—how do you say “my schedule is full”? You know they’re not being unreasonable. The system that gave them one hour a week to process decades of trauma is being unreasonable.

And yes, some clients are manipulative. Addiction encourages manipulation. I’m not naive about that. But when you’re already second-guessing yourself about whether you’re being too rigid, it’s hard to tell the difference between someone genuinely in crisis and someone who’s learned that crisis language gets them what they want.

Then there’s countertransference—which is just a fancy way of saying your own stuff gets activated. Maybe this client reminds you of your brother who overdosed. Maybe they’re the same age you were when everything fell apart. Maybe you’re trying to save them because you couldn’t save yourself back then.

That’s not a boundary problem. That’s unprocessed personal work showing up in your clinical decisions. And if you don’t recognize it, you’ll say yes to things that aren’t about this client at all. As we discussed in “I’m Making It Worse,” sometimes our fear of harm is really about our own unresolved experiences.

And the biggest reason saying no is hard?

The Systemic Failure You Can’t Unsee

The system is genuinely failing people, and you can SEE it.

You’re not imagining it. SAMHSA’s behavioral health workforce reports confirm what we already know: caseloads are too high, funding is too low, and clients fall through cracks because there aren’t enough resources, enough staff, enough time. And when you’re standing in that gap, watching someone struggle, it FEELS like saying no means letting them fall.

But here’s the part I’m still working through:

Your yes doesn’t fix the system. It just keeps you (and sometimes them) functional enough that the system doesn’t have to change.

I don’t have an answer for that yet.

What Actually Helped (Not the Platitudes)

I’m not going to give you five perfect strategies for setting boundaries. I don’t have five perfect strategies. What I have is messy, incomplete trial-and-error that eventually added up to something workable.

I Had to Decide What I Was Actually Protecting

For a long time, I thought the choice was: clients’ needs vs. my comfort.

And when you frame it that way, of course you choose clients. Who picks their own comfort over someone else’s survival?

But that wasn’t the real choice.

The real choice was: helping this client today vs. being available to help clients tomorrow (and next week, and next year). Being generous with this person vs. being present for my daughter. Doing more than my job required vs. doing my job sustainably.

When I reframed it that way, the decisions got clearer. Not easier. Clearer.

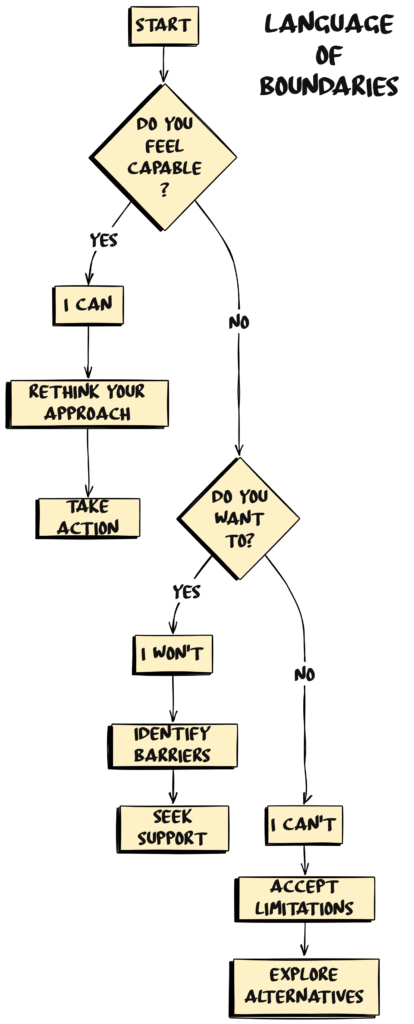

I Started Saying “I Won’t” Instead of “I Can’t”

“I can’t” implies you would if you could. It leaves room for negotiation. It makes clients think if they push harder or explain better, you’ll find a way.

“I won’t” is a decision, not a limitation.

“I can’t” language:

- “I don’t have availability this week.” (Implies: maybe next week?)

- “My schedule is full.” (Implies: if something opens up?)

“I won’t” language:

- “I don’t provide that service, but here’s who does.”

- “That’s outside the scope of our work together.”

- “I don’t extend sessions past the scheduled time.”

You don’t have to justify “I won’t” with exhaustive explanations. You can simply decline and redirect.

I’m still not great at this. But I’m better than I was.

I Pre-Decided Some Things

Decision fatigue is real. When you’re making dozens of clinical decisions daily—safety assessments, crisis interventions, boundary calls with hostile family members—and then ALSO having to decide in the moment whether you can take on one more thing, you’ll default to yes. Not because you’re not thinking, but because you’ve already spent your decision-making energy on actual clinical work.

I learned this the hard way.

After that debacle with the family and their requested letter I decided in advance:

- Court letters: I need real time to write something useful. A week minimum, ideally more. If someone’s asking for overnight turnaround, I know from experience I either won’t deliver or I’ll deliver something rushed that doesn’t actually help them. So now I ask: “When’s your court date?” and work backward from there. Sometimes there are exceptions—actual emergencies where I can shuffle things—but “I forgot to ask you sooner” isn’t one of them.

- High-risk transports: I generally don’t take high-risk clients without administrative sign-off, but it depends. If I know the client well, if I’ve worked with them on behavior plans, if the risk is manageable—that’s different than someone new with a history I don’t know. The question became: do I have enough information and support to do this safely? Not just “can I technically handle it,” but “should I be doing this without backup?”

- After-hours contact: I had to get clear on what actually constitutes an emergency. “I’m having thoughts of hurting myself” at 9 PM? That’s an emergency. “Can you write me a letter?” at 9 PM? That can wait until tomorrow. But it’s not always that clean. Sometimes “I’m really struggling tonight” is code for “I need someone to know I’m not okay,” and that’s worth responding to. I learned to trust my assessment of what’s happening, not just apply a blanket rule.

- Session length: I try to end on time because otherwise my whole day cascades into chaos. But if we’re 5 minutes from a breakthrough, or someone’s in the middle of processing something significant, or there’s genuine distress—I stay. The boundary isn’t “exactly 50 minutes no matter what.” It’s “I don’t extend sessions just because someone wants to keep talking when we’ve already covered what we needed to cover.”

The point isn’t to have perfect rules. The point is to reduce the number of times I’m making these decisions from scratch in the moment when I’m already exhausted.

Having thought through the general framework means I can make exceptions when they make sense—but I’m making them intentionally, not defaulting to yes because I haven’t thought it through.

I Tracked What My “Yes” Actually Cost

You think you’re just saying yes to one thing. But that one thing has a cascade of consequences.

When I said yes to scheduling every hour, I stayed until 2 AM documenting. I missed time with my daughter. My fibromyalgia flared. I cried from exhaustion. My relationship with my daughter suffered.

When I said yes to buying group supplies, I spent money I didn’t have. I reinforced the expectation that I’d always provide this. Other staff didn’t step up because they knew I would.

I don’t regret all of those yeses. But I needed to see the full price I was paying for them.

I Let My Body Force the Boundary My Mind Couldn’t Set

I started saying no when it became harder to wake up in the morning.

After 20+ days without a break, I’d cry from exhaustion. But I’d known those costs the whole time. I’d been managing them. What changed wasn’t that my body suddenly “woke me up” to something I’d been denying.

What changed was that my daughter was getting older. The relationship gap was widening. And the window to repair it was closing.

The work would always be there. High-risk clients would always need transport. Groups would always need supplies. The system would always be failing people.

But my daughter would only be this age once.

So I shifted. Not because my previous choices were wrong—they were strategic decisions made with available information and capacity. But because the variables changed, and so did my priorities.

That’s not “finally learning boundaries.” That’s adapting your strategy when circumstances change.

Your body doesn’t “force” boundaries when you’re too incompetent to set them yourself. Your body gives you information. And you—as a skilled professional who’s been making informed trade-offs all along—decide what to do with that information.

From Blog Post to Your Office

This blog gives you the “why” and “how.” The New Clinician Survival Kit gives you the “what”—actual tools delivered quarterly.

⭐ Specialty Edition (This Quarter)

- 90-Day Clinician Survival Planner – Track boundaries, self-care, and professional goals

- Supervision Prep Pad – Organize thoughts before meetings

- Client Response Bookmark – Common phrases clients say + general responses

- Office Politics Sticker – Reminder of professional behavior

- 4 Pages of Organizational Stickers – Caseload tracking, report reminders, and more

- Digital Resources Library – Templates, guides, and reference materials

Professional Edition also available (1 physical item + digital resources)

The Part Nobody Talks About When Setting Boundaries With Clients

Most boundary advice assumes the problem is you.

You’re too nice. Too helpful. Too unable to say no. You need to work on yourself, get therapy, learn assertiveness.

And maybe that’s true. Many of us do have personal work to do around boundaries.

But also?

The system is designed to exploit people who care.

Agencies know that counselors who are committed to clients will work overtime without pay. Will spend their own money on supplies. Will take on extra cases because they can’t stand to see someone go without services.

And instead of fixing the system so those things aren’t necessary, they just… let you do it. Because it’s cheaper than hiring more staff. Easier than fighting for better funding. More sustainable (for them) than addressing the actual problem.

Your boundary issues keep the system functional.

And I don’t know what to do with that information except to say: if you’re working yourself into the ground and feeling guilty about even considering saying no, maybe the problem isn’t entirely you.

Maybe the problem is that you’re trying to provide adequate services within a system designed for inadequate care.

And no amount of personal boundary work fixes that. Professional organizations like NAADAC are finally starting to emphasize that setting boundaries with clients is about systemic sustainability, not individual self-care failures.

What I’d Tell That Version of Myself at 1 AM

I wouldn’t tell you to work less. You wouldn’t listen anyway—and honestly, I’m not sure I’d want you to. You’re 26. You have the energy. The systems you’re building right now? You’ll use them for the next 15 years. The efficiency you’re learning actually matters.

But I would tell you this, and I’d make sure you heard me:

Your child is only going to be this age once.

The client you’re documenting for at 1 AM? You’ll have other clients. You’ll have other chances to help people. The work will always be there.

But your daughter won’t always be two, three, four. She won’t always be learning to walk, learning to talk, reaching for someone.

And one day she’ll reach for someone else because you’ve taught her that’s who shows up.

I wouldn’t tell you to stop working hard. But I would tell you to go home at a reasonable hour more often than you do.

Because the only regret you’ll have—the only one that will actually matter when you look back—is missing her.

When Setting Boundaries with Clients Feels Impossible

Maybe you do. Maybe your financial situation requires two jobs. Maybe your agency is understaffed, and clients will literally go without services if you don’t stay late. Maybe you’re the only one willing to do the hard cases, and if you stop, no one else will step up.

I’m not going to tell you you’re wrong. I don’t know your situation.

But I am going to tell you this:

If you’re going to work this hard, at least be strategic about it.

Build systems that make the work more efficient. Document as you go instead of staying until 2 AM catching up. Use templates, checklists, frameworks that reduce decision fatigue.

If you’re going to give 110 percent, do it in a way that’s sustainable for longer than a few months.

And watch for the warning signs that your body is forcing a boundary your mind can’t set. The crying outbursts. The inability to wake up. The moment when your kid reaches for someone else.

Those signs mean something. Don’t ignore them until you don’t have a choice.

Setting Boundaries with Clients: Moving Forward

I don’t have a neat conclusion for this. I don’t have five action steps that will fix everything or a perfect framework for when to say yes and when to say no.

What I have is this:

- You’re allowed to work hard. You’re allowed to care deeply. You’re allowed to go above and beyond when you actually have the energy for it.

- And you’re also allowed to go home at 5 PM—even though that means the client calling at 5:30 won’t get a same-day response. Even though another counselor might not pick up your high-risk case. Even though it feels like you’re letting people down.

- I don’t have a clean answer for how to live with that tension. I just know that both things are true: the work matters, and you matter. The system wants you to pick one. You don’t have to.

The problem isn’t you working too hard or not hard enough. The problem is a system that makes “adequate client care” and “counselor sustainability” feel like opposing choices.

They shouldn’t be. But here we are.

So, if you’re working yourself into the ground right now, I’m not going to judge you for it. I did it too. And I’d do parts of it again.

But I’d also tell you: watch for the costs you’re not accounting for. The relationships you’re missing. The body that’s paying a price.

Because some of those costs can’t be recovered later.

And you deserve to know what you’re actually trading.

I created The Underrated Superhero to support clinicians doing this work—because this population needs counselors who can sustain the intensity long-term. That only happens when you have real tools, honest conversations about the systemic problems, and permission to make strategic choices about your energy. That’s what I’m building here.

💬 What’s the hardest “no” you’ve ever had to say? Drop a comment below.

Next Week: We’re tackling another brutal truth that keeps clinicians up at night. See you then!

Until Next Week | The Underrated Superhero

© 2025 The Underrated Superhero LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Resources Referenced in This Post

- APA: Better Boundaries in Clinical Practice – Research on professional boundaries in therapy and why clear limits are easier to maintain than subtle boundary decisions

https://www.apa.org/topics/psychotherapy/better-boundaries-clinical-practice - SAMHSA: Behavioral Health Workforce Report 2024 – Data confirming workforce shortages, high caseloads, and inadequate funding in behavioral health systems

https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/state-of-the-behavioral-health-workforce-report-2024.pdf - NAADAC: Professional Wellness and Self-Care – Resources emphasizing that setting boundaries is about systemic sustainability, not individual failure

https://www.naadac.org/professional-wellness - American Psychological Association: Psychologist Burnout – Research on how systemic factors contribute to clinician burnout and impact on client care

https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/01/special-burnout-stress

Previous posts in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series:

Week 1: I Hate Group Therapy: How I Went from Dreading sessions to Loving Them

Week 2: I Can’t Do This: When Imposter Syndrome for Therapists Hits Hardest

Week 3: My Client Hates Me: When Resistance Feels Personal

Week 4: I’m Making It Worse: Fear of Harming Clients