Fear of Being Reported

It’s 3 AM and you’re lying awake replaying the session.

Did you document that correctly? Should you have called DCFS? And if the client complains? But what if your supervisor disagrees with your clinical judgment? What if someone reports you to the board?

Your license, your career, your ability to pay your bills—all of it hangs by a thread, dependent on…

If you’ve ever lost sleep over the fear of being reported—to the licensing board, to DCFS, to your supervisor, to anyone with the power to end your career—you’re not alone. In fact, you’re probably not actually doing anything wrong.

📚 This is Blog #6 in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series (Click to explore the series)

Weekly honest support for the struggles every clinician faces: “I hate group therapy.” “I can’t do this.” “My client hates me.” “I’m making it worse.” “I can’t say no.” “They’re going to report me.”

These aren’t signs you’re failing. They’re signs you’re human.

A note before we begin: The stories in this post are real, but I’ve changed details to protect privacy—mine and others. What matters isn’t the specifics. It’s the pattern underneath.

Why the Fear of Being Reported Shows Up in Our Field

Our own wounds, our own experiences with pain and healing often draw us to this work. That creates deep empathy and clinical insight.

It also means some people in positions of power handle that power… poorly.

Especially during transitions.

I’ve watched this pattern play out over and over: a clinician leaves a position—to start a business, take another job, relocate, whatever the reason—and suddenly the supervisor or practice owner reacts in ways that seem disproportionate. Accusations appear. Someone scrutinizes past work. Things that worked fine for years suddenly become “concerning.”

Maybe it feels like abandonment to them. Or they’re threatened by the change. Or they’re dealing with their own burnout and you became the target. I don’t know why it happens.

Nevertheless, I do know it happens often enough that if you’re experiencing it right now, you need to hear this: you’re probably not doing anything wrong.

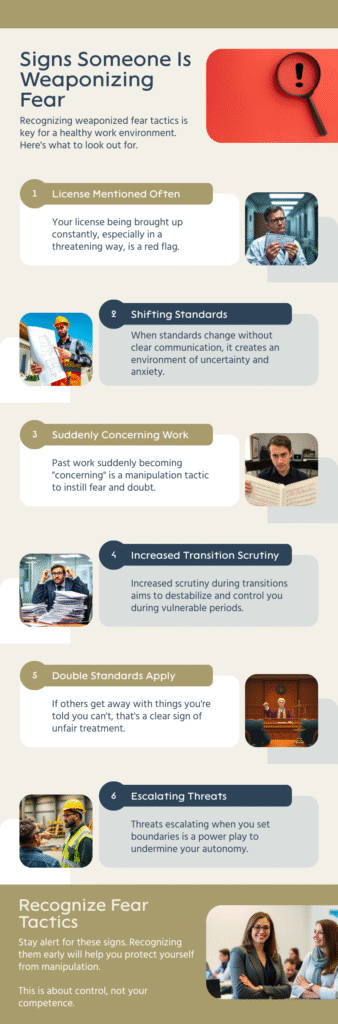

When “You Could Lose Your License” Gets Weaponized

Earlier in my career, I was transitioning out of a position. I’m keeping some details vague—not to protect anyone, but to protect myself.

During the transition, I made what I thought was a supportive statement to clients about their upcoming transfers to new clinicians. My supervisor told me this wasn’t protocol—that the new clinician should handle those conversations, not me during termination. I understood her point and corrected it immediately with clients.

But then things got complicated.

When I communicated what the supervisor had told me was protocol, she accused me of lying—of telling clients things were policies when they weren’t. The story changed. She turned clear guidance into something I’d apparently fabricated

Then, when a client couldn’t meet with me before my departure (circumstances beyond my control), she told me I’d handled it unprofessionally.

After I left, I learned that she’d told multiple former clients that what I’d done “could have cost me my license.”

I fell into a depression. Questioned everything about myself. I couldn’t even talk about it.

Looking back, here’s what I know now that I wish I’d known then: I wasn’t ever in actual fear of being reported to the licensing board. Not really. Because when I stepped back and looked at what I’d actually done, I knew I could argue every decision I’d made.

The accusations weren’t about ethics. They were about control, power dynamics, and someone reacting badly to a transition they didn’t want.

But in the moment? I couldn’t see that clearly. If this sounds familiar, you might also relate to what I wrote about making clients worse—that same spiral of questioning every clinical decision you’ve ever made.

The Gray Areas That Trigger the Fear of Being Reported

Nevertheless, the fear of being reported isn’t always about false accusations from supervisors. Sometimes it’s about the legitimate gray areas where you have to make judgment calls with incomplete information.

Let me give you some real examples.

The 17-Year-Old and the Mandated Report Question

I had a 17-year-old client who was pregnant. The father was 19.

Technically, I could have called DCFS. Age difference, minor, all of that.

But here’s what else was true: The client had told her parents. Both sets of parents supported her actively. She attended all prenatal appointments. She’d decided to continue the pregnancy and was attending school regularly. She was abstaining from substances. The boyfriend wasn’t engaging in any high-risk behavior around her.

I didn’t call.

Did I second-guess myself? Absolutely. I was nervous because it was a gray area. But I also believe it’s important to live in the gray rather than strict black and white—to use clinical judgment rather than just following a checklist.

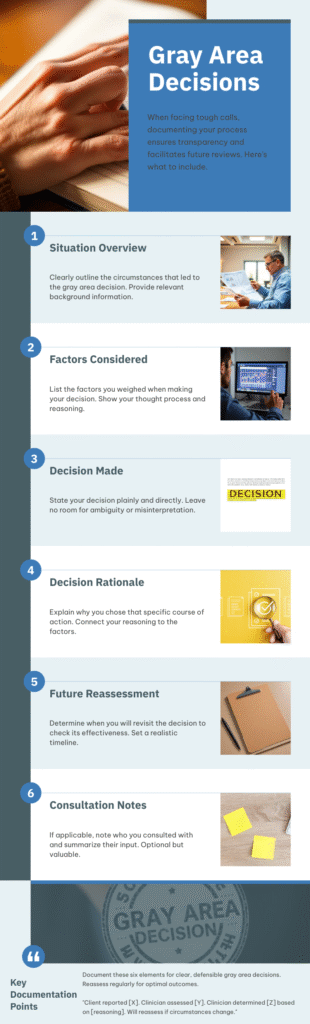

I documented my reasoning: “Clinician did not report this due to [detailed reasons]. If situation changes, clinician will reassess.”

If someone had reported ME for not calling DCFS in that situation, I would have said exactly what I wrote in my notes. I trusted my judgment. Still, I took a gamble. Because I didn’t know everything about the situation.

That’s the thing about gray areas: you do your best with the information you have, and you document your clinical reasoning. Understanding your state’s mandated reporting requirements helps you know where the actual legal lines are versus where clinical judgment applies.

The CYA Calls

On the flip side, I called DCFS several times knowing it probably wouldn’t go anywhere. Times when the law required me to call, I made the call, and DCFS told me “We’re not going to pursue this.”

Even mandated reporting isn’t as black and white in real life as it sounds in training. There aren’t enough DCFS caseworkers to follow up on every case. Consequently, they triage. DCFS often doesn’t pursue cases that are ‘just on the cusp.'”

Therefore, yes, I’ve made several CYA (Cover Your Ass) calls. Calls where I doubted anything would come from them, but I needed to document that I’d fulfilled my legal obligation.

Did it feel like a waste of time? Sometimes. But it was still necessary to be clear in my documentation.

What ACTUALLY Gets People Reported (And What Doesn’t Trigger the Fear of Being Reported)

After years in this field, here’s what I’ve learned about what actually triggers licensing board complaints versus what new clinicians are terrified of:

Real Violations That Get People Reported:

- Boundary violations – Sexual relationships with clients, dual relationships that harm clients, financial exploitation

- Abandonment – Terminating abruptly without referrals, ghosting clients, not providing crisis coverage

- Fraud – Billing for services not provided, falsifying documentation, insurance fraud

- Practicing outside your scope – Providing services you’re not trained or licensed to provide

- Gross negligence – Ignoring clear safety risks, not following up on SI/HI, missing obvious red flags repeatedly

The American Counseling Association’s Code of Ethics and your state licensing board provide clear guidance on what constitutes actual ethical violations.

Things That Feel Scary But Usually Aren’t Board-Level Issues:

These situations rarely result in licensing board action:

- Policy disagreements with your employer (like my transition situation)

- Clinical judgment calls in gray areas (like the pregnant 17-year-old)

- Client complaints about your approach, personality, or therapeutic style

- Documentation that’s “good enough” rather than perfect

- Setting boundaries that clients don’t like

The difference: Actual ethical violations harm clients or violate laws. Everything else is usually just… clinical practice. Messy, complicated, imperfect clinical practice.

How to Protect Yourself from the Fear of Being Reported Without Paralyzing Yourself

Here’s my approach, learned through experience:

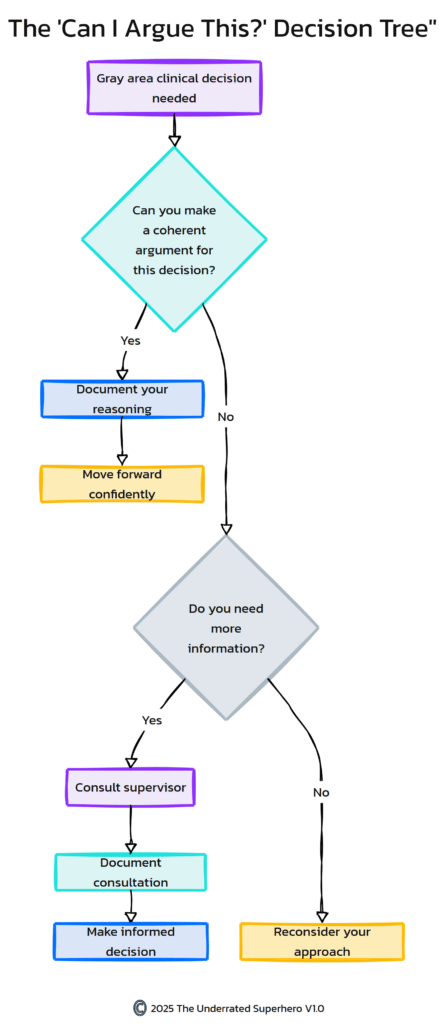

1. The “Can I Argue This?” Test

Before you make a decision in a gray area, ask yourself: “If I had to defend this decision to my licensing board, could I argue my reasoning?”

Not “is this the only right answer?” Not “would everyone agree with me?” Just: Can I make a coherent argument for why this was clinically appropriate given what I knew at the time?

- If yes, document your reasoning and move forward.

- If no, consult with someone or reconsider your approach.

Document Factually, Not Defensively

Write what happened and why you made the clinical decisions you made. Don’t add extras. Don’t write like you’re defending yourself in court—that actually makes things look worse.

Just facts and clinical reasoning.

“Client reported [situation]. Clinician assessed [factors]. Clinician determined [decision] based on [reasoning]. Will reassess if circumstances change.”

That’s it.

Consult When You’re Unsure

I often ran pros and cons in my head for gray area decisions. If I was really concerned about what I should do, I asked my supervisor.

Not to get “permission” or to pass off responsibility. To get another clinical perspective and to document that I’d consulted.

“Discussed case with clinical supervisor on [date]. Supervisor agreed with clinical approach” goes a long way if anyone ever questions your judgment.

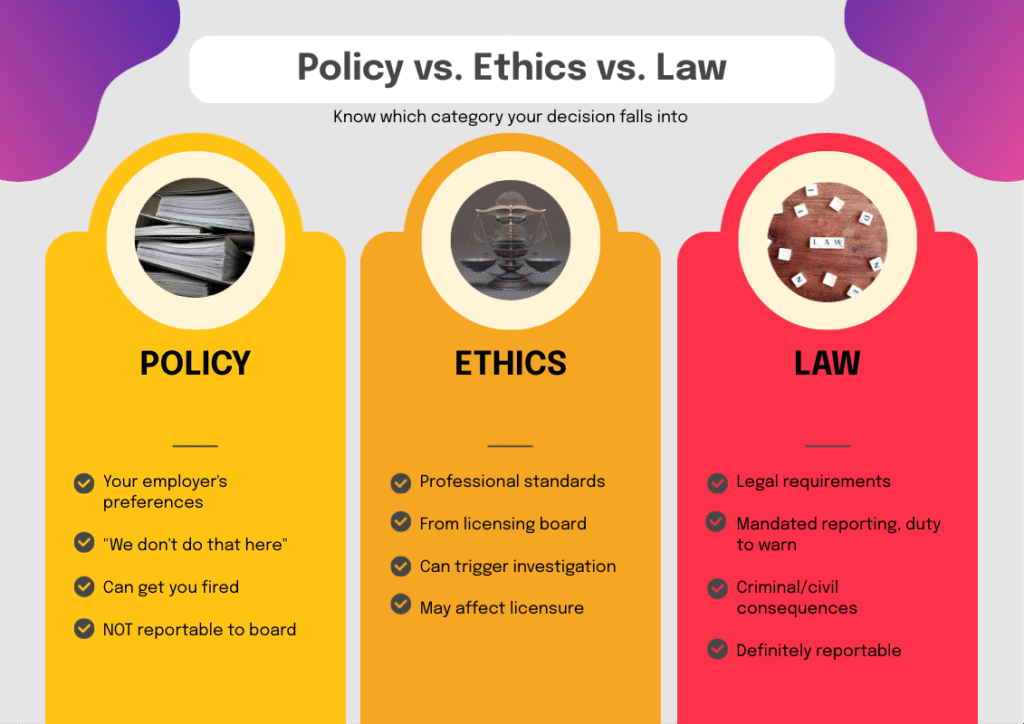

4. Know the Difference Between Policy, Ethics, and Law

- Policy = Your employer’s preferences (“we don’t do that here”)

- Ethics = Professional standards from your licensing board

- Law = Actual legal requirements (mandated reporting, duty to warn, etc.)

Your employer can fire you for violating policy. But they can’t report you to the board for it unless it’s also an ethical or legal violation.

My transition situation? That was policy. Not ethics. Not law.

5. Keep Records of Important Conversations

After my experience, I now keep records of what people say—especially supervisors—in case they try to manipulate the situation later.

Email summaries after verbal conversations: “Per our discussion today, my understanding is [X]. Please let me know if I’ve misunderstood.”

Does it feel overly cautious? Maybe. But when someone blatantly changes their story and you have no documentation, you’re stuck.

The Reality Check You Need About the Fear of Being Reported

Here’s what I wish someone had told me when the fear of being reported was keeping me up at night:

Most threats of “I’m going to report you” or “you could lose your license” are manipulation, not reality.

Clients threaten it when they’re angry. Family members threaten it when they disagree with your treatment approach. Employers weaponize it when they want control.

Actual licensing board complaints are rare. And even when they happen, the board investigates. They look at your documentation, your reasoning, the context. They’re not looking to take away licenses over judgment calls made in good faith.

- You can’t control whether someone reports you. Truly. Someone could file a frivolous complaint tomorrow for reasons that have nothing to do with your actual practice.

- What you CAN control: Whether you’re practicing ethically, documenting appropriately, consulting when needed, and trusting your clinical judgment in gray areas.

When the Fear of Being Reported Becomes Paralyzing

Healthy professional caution looks like:

- Documenting your clinical reasoning

- Consulting on complicated cases

- Following mandated reporting laws

- Setting appropriate boundaries

- Staying within your scope of practice

Paralyzing professional anxiety looks like:

- Losing sleep over every clinical decision

- Second-guessing yourself constantly

- Making decisions based on fear rather than clinical judgment

- Avoiding necessary interventions because you’re scared of complaints

- Feeling like you’re one mistake away from losing everything

If you’re in the second category, your competence isn’t the problem. Instead, it might be:

- A toxic work environment that weaponizes fear

- Lack of adequate supervision and support

- Burnout affecting your confidence

- Past trauma (professional or personal) making everything feel high-stakes

Consider: Is the environment you’re in safe enough for you to practice with reasonable confidence? Or is someone keeping you afraid on purpose?

The National Alliance on Mental Illness provides resources for mental health professionals dealing with workplace stress and professional anxiety.

What I’d Tell You If You Were Sitting Across from Me Right Now with the Fear of Being Reported

If you came to me tomorrow and said, “I’m terrified of being reported,” here’s what I’d tell you:

- First: Tell me what happened. What specifically are you afraid you did wrong?

- Second: Let’s look at whether this is an actual ethical violation, a policy disagreement, or a clinical judgment call in a gray area.

- Third: Can you argue your reasoning? If yes, you’re probably fine. If no, let’s figure out what you’d do differently next time and document the learning.

- Fourth: Is someone using “you could lose your license” to control or manipulate you? Because that’s not about your competence—that’s about them.

- Fifth: You’re going to make mistakes. We all do. The question isn’t whether you’ll ever make a wrong call—it’s whether you’re practicing thoughtfully, ethically, and with good intent. That’s what matters.

You’re Not Alone in the Fear of Being Reported

Almost every clinician I know has had a moment—or many moments—of lying awake worried about being reported. About losing their license. About that one decision coming back to haunt them.

It’s part of the territory when you’re responsible for people’s wellbeing and navigating complex systems with imperfect information.

But here’s what I want you to know:

The fear of being reported doesn’t mean you’re doing something wrong.

It means you care deeply about doing right by your clients and protecting your ability to keep serving them.

And most of the time, the thing you’re terrified of? It’s not actually going to happen.

What Comes Next

I left that position. The one where I was told I could lose my license over what amounted to policy disagreements and power dynamics.

I had already decided to transition running The Underrated Superhero full-time before any of that happened. The toxic situation didn’t drive me out—I was leaving anyway.

But the way it ended tried to make me question whether I deserved to work in this field at all.

Here’s what I know now: I wasn’t driven out. I evolved. I’m still serving the field, just differently. And I’m creating the resources I wish had existed when I was drowning in professional fear.

You don’t have to leave direct practice like I did. But you do need to know: if someone is weaponizing “you could lose your license” to control you, that says everything about them and nothing about your competence.

Trust your clinical judgment. Document your reasoning. Consult when you’re unsure. And know the difference between actual ethical violations and someone trying to make you feel small.

Resources to Support You

If you’re dealing with the fear of being reported right now, here’s what might help:

📧 Subscribe to the New Clinician Survival Kit Series – Weekly honest support for the struggles every clinician faces. Subscribe here

🛠️ Get the New Clinician Survival Kit – Physical tools and resources to support you through your first years in the field. Includes Quick Capture documentation tools, decision trees, and practical frameworks for navigating these exact situations. Shop now

📚 Explore Our Free Tools with an account sign-up – Access free resources including decision trees, clinical frameworks, and support guides. Browse free tools.

💬 You’re Not Alone – Share your experience in the comments below. Have you been threatened with being reported? How did you handle it?

Next Week: We’re tackling another brutal truth that keeps clinicians up at night. See you then!

Until Next Week | The Underrated Superhero

© 2025 The Underrated Superhero LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Resources Referenced in This Post

- Child Welfare Information Gateway: Mandated Reporting by State – Comprehensive state-by-state guide to mandated reporting laws, definitions, and requirements for child abuse and neglect

https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/laws-policies/state/ - American Counseling Association: Code of Ethics (2014) – Complete ACA Code of Ethics providing clear guidance on ethical standards, boundary violations, and professional conduct for counselors

https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/ethics/2014-aca-code-of-ethics.pdf - National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) – Resources for mental health professionals dealing with workplace stress, professional anxiety, and maintaining wellness in clinical practice

https://www.nami.org/ - Virtual Lab School: Child Abuse Identification and Reporting – Educational resource on understanding child abuse definitions, mandated reporting requirements, and state-specific guidelines

https://www.virtuallabschool.org/infant-toddler/child-abuse-identification-and-reporting/lesson-3

Additional Support from The Underrated Superhero

- 📚 Quick Capture Progress Note System – Documentation tools that help you document efficiently without defensive over-explaining

- 🛠️ New Clinician Survival Kit – Physical tools including decision trees and frameworks for navigating gray area situations

- 📝 Free Clinical Tools – Access free resources including decision trees, clinical frameworks, and support guides. Requires free account.

- 📧 Subscribe to the New Clinician Survival Kit Series – Weekly honest support for the struggles every clinician faces

Previous posts in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series:

Week 1: I Hate Group Therapy: How I Went from Dreading sessions to Loving Them

Week 2: I Can’t Do This: When Imposter Syndrome for Therapists Hits Hardest

Week 3: My Client Hates Me: When Resistance Feels Personal

Week 4: I’m Making It Worse: Fear of Harming Clients

Week 5: I Can’t Say No: Setting Boundaries with Clients