Counselor Doesn’t Like Client

Sometimes you just don’t like your client.

Not “challenging.” Not “difficult.” Not “presenting with complex trauma and attachment issues.” You just don’t like them. You see their name on your schedule and your whole body tenses up. You catch yourself hoping they cancel. And then you feel like garbage about it because what kind of therapist even thinks like that?

I’ve been there. More than once, honestly.

📚 This is Blog #15 in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series (Click to explore the series)

Weekly honest support for the struggles every clinician faces: “I hate group therapy.” “I can’t do this.” “My client hates me.” “I’m making it worse.” “I can’t say no.” “They’re going to report me.” “I’m too tired to care.” “What do I even say?” “I don’t know enough.” “They keep relapsing.” “Am I documenting wrong?” “My supervisor doesn’t get it.” “I can’t handle this caseload.” “Nobody told me about the paperwork.” “I don’t like my client.”

These aren’t signs you’re failing. They’re signs you’re human.

When a Therapist Doesn’t Like a Client

One client, I knew they had a crush on me.

Every session I was on guard—watching my words, my body language, making sure nothing could be misinterpreted as encouragement. It wasn’t even about the clinical work at that point. It was just exhausting being so vigilant all the time. I’d leave those sessions drained in a way that had nothing to do with the actual therapeutic content.

When they finally told me how they felt, I handled it by the book. Normalized their feelings, reestablished boundaries, reminded them nothing could be reciprocated. We had the conversation they teach you about in grad school—the one about dual relationships and appropriate boundaries. I didn’t freak out. I was actually proud of how I managed it.

And when they decided to stop coming?

Yeah. I was relieved. I’m not going to sit here and pretend I wasn’t.

The Client Who Didn’t Talk

Then there was the client who just… didn’t talk.

I was pulling teeth every session trying to get anything going. Open-ended questions got one-word answers. Silence stretched into awkwardness. I’d try different approaches—reflective listening, Socratic questioning, just sitting with the silence—and nothing really landed.

And the thing is, they loved coming. They wanted to keep meeting. They’d show up every week, on time, ready for their session. So it went on for a couple years.

I found myself doing things I’d never do with other clients. Offering to reschedule at the smallest hesitation on their end. Feeling relieved when they mentioned they might be busy next week. Watching the clock in a way I didn’t with anyone else.

I was tired in those sessions. Withdrawn. Going through the motions.

I carried that quietly for a long time because it didn’t feel serious enough to bring to supervision. It was just… I didn’t like them. That felt like a stupid reason to use up consultation time when other clinicians were dealing with actual crises.

You Don’t Have to Like Every Client

Here’s what took me years to actually believe, and I’m still working on it if I’m being honest—you don’t have to like a client to help them.

Research backs this up. Dislike of a client is something clinicians encounter all the time. It’s not rare. It’s not a sign you’re broken. And there are ways to work through it without it tanking the treatment.

But we don’t talk about it.

We feel guilty. We assume something’s wrong with us. We think good therapists connect with everyone, and if we don’t, we must be failing somehow.

The Flip Side of “My Client Hates Me”

I wrote about the flip side of this in My Client Hates Me—that feeling when you sense rejection or disconnect from the client’s end. When you walk out of a session convinced they can’t stand you.

This is different though. They’re fine with you. They keep showing up. They want to be there.

You’re the one struggling. And somehow that feels worse?

We get caught up in our own stuff. Am I connecting enough? Do they like me? Am I even good at this? What’s wrong with me that I dread seeing this person?

And we forget—it’s not about us.

If the client feels a connection and they’re making progress, that’s enough. What I feel about them doesn’t have to be part of the equation.

It took me a long time to get there. Many therapists never do.

What If You Can’t Just Refer Out?

In community mental health—which is where a lot of my experience is—you don’t really have the option to just refer out because someone annoys you.

There isn’t another therapist waiting in the wings to take them. Caseloads are full. Waitlists are long. Discharging a client because you don’t vibe with them means they might have very few other options. Maybe no other options.

So you figure it out. You meet with them. You do the work even when you don’t feel like it.

Finding What Works When You’re Stuck

With that quiet client, I tried different stuff.

Card games instead of just talking. Coloring. Going for walks instead of sitting in my office. Trying to find something—anything—that pulled them out a little bit.

Some of it worked, I guess. Or at least something was working. They kept coming back for years, and they seemed to be getting something out of it even if I couldn’t always see what.

I was proud of myself when I realized I could still make a difference with clients I wasn’t a fan of. That quiet client made progress. Not dramatic, headline-worthy progress. But steady, quiet growth that happened over time.

That taught me something important: my feelings about them weren’t the determining factor in whether therapy worked.

When Does Disliking a Client Become a Problem?

But here’s where I need to be honest about something.

There’s a difference between “I don’t like this client” and “my dislike is actually hurting this client.”

First one is human. Second one is a problem.

And the line between them isn’t always obvious when you’re in it.

The APA talks about this—countertransference is normal. Inevitable, even. Every therapist experiences emotional reactions to their clients. That’s not the issue.

It becomes an issue when you’re not managing it. And managing doesn’t mean stuffing it down or pretending it’s not there. It means actually looking at it.

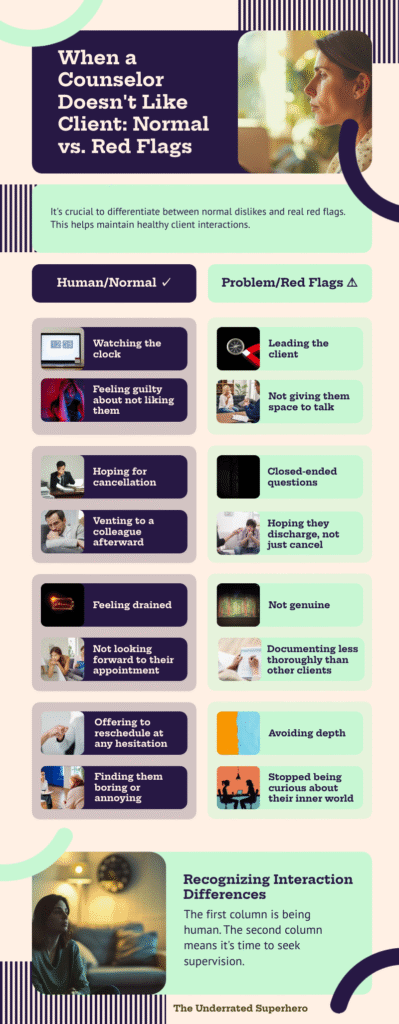

Red Flags Your Feelings Are Impacting Treatment

So like… when does it cross the line?

I think about it this way. If you’re not giving them space to talk—if you’re jumping in too quickly or cutting them off—that might be you trying to control the session because you’re uncomfortable. If you’re leading them instead of letting them lead. Using closed-ended questions because you don’t actually want them to elaborate on anything.

Being judgmental. Rolling your eyes internally at things they say. Not being genuine—performing empathy instead of actually trying to understand them.

That’s not just being tired or watching the clock. That’s your stuff getting in the way of their treatment. And that’s different.

Other signs to watch for:

- You’re avoiding depth. You keep things surface-level because you don’t want to engage more than you have to.

- You’re hoping they discharge. Not just feeling relieved when they cancel, but actively hoping they’ll decide to stop coming.

- You’re less curious. With clients you like, you want to understand them. With this client, you’ve stopped wondering about their inner world.

- You’re documenting differently. Your notes are shorter, more clinical, less detailed. You’re not capturing the nuance you would with someone else.

- You catch yourself being sarcastic or dismissive. Even just in your head.

✅ Self-Check: Is This Normal or a Red Flag? (Click to expand)

Check any that apply to how you’re feeling about this client:

Human & Normal ✓

Red Flags ⚠️ — Time to Seek Supervision

If you checked items mostly in the first section: You’re human. Keep showing up.

If you checked items in the second section: It’s time to bring this to supervision or consultation.

The Guilt and Shame Are Normal Too

Research on countertransference shows therapists commonly feel guilt and shame around negative reactions to clients.

Which, yeah. That tracks.

I felt terrible about dreading that quiet client. I knew they enjoyed our sessions. I knew they were showing up consistently, which for some people is huge. And I was sitting there wishing they’d cancel.

The problem isn’t having the feelings though. It’s not doing anything about them.

What to Do When You Notice It

If you notice it’s happening—sit with it first.

Don’t immediately jump to “I need to transfer this client” or “I’m a terrible therapist.” Just notice it. Get curious about it.

Ask Yourself Some Questions

Is this about them, or is this about me?

Sometimes we dislike clients because they remind us of someone. An ex. A family member. A version of ourselves we don’t like. That’s worth exploring.

Sometimes we dislike clients because they’re actually being difficult—hostile, manipulative, boundary-pushing—and our reaction is appropriate. That’s different.

Sometimes we dislike clients because we’re burned out and everyone is irritating us right now. That’s a different problem entirely.

What specifically bothers me about them?

If you can name it, you can work with it. “They talk too much” is different from “they remind me of my mother” is different from “they’re racist and I’m trying to stay professional.”

Is this impacting the treatment?

Be honest. Are they still making progress? Do they seem to feel supported? Or has the therapeutic relationship actually deteriorated?

Then Get Support

Bring it to supervision or talk to a colleague you trust.

I know I said earlier that I didn’t bring up the quiet client because it felt too minor. Looking back, I probably should have. Not because it was a crisis, but because talking it through might have helped me show up better for them.

If you have access to consultation, use it. This is exactly what it’s for.

When It’s Time to Refer

And if you genuinely can’t get past it—if your bias or countertransference is impacting the relationship in ways you can’t fix—then the client deserves a referral.

Not because you don’t like them. Because they’re not getting what they need from you.

That’s the line, I think. It’s not about whether you like them. It’s about whether they’re actually benefiting from working with you.

In my case, I had to make that call once. Not because I didn’t like the client—the adolescent was fine. But the father was violent, aggressive, disrespectful. I wasn’t going to be abused. I told my supervisor I couldn’t continue with that family, and we made other arrangements.

That wasn’t about preference. That was about safety. But the principle is similar: sometimes the right thing is to step back.

It’s Not About You

I still get uncomfortable when I notice annoyance creeping in with a client. I hate it, actually. I wish I connected with everyone. I wish I walked into every session feeling curious and engaged and fully present.

But I don’t. Because I’m human. I have my own stuff. We all do.

If you’re dealing with this on top of feeling like you’re making things worse or being too tired to care, that’s a lot to carry. Might be worth looking at whether something bigger is going on—burnout, compassion fatigue, whatever.

But disliking a client by itself isn’t a crisis. It’s just being a person.

What I’d Tell Early-Career Me

If I could go back and tell early-career me one thing about this, it would be simple:

It’s not about you.

You can dislike a client and still be excellent at your job. You can dread a session and still show up fully. You don’t have to feel warm and fuzzy about everyone to help them.

The work is what matters. Not your feelings about doing it.

Just make sure your feelings stay yours. Process them somewhere—supervision, consultation, your own therapy, a trusted colleague. Don’t let them leak into the room and become the client’s problem.

That’s the line. And once you know where it is, the guilt gets a lot lighter.

That wasn’t about preference. That was about safety. But the principle is similar: sometimes the right thing is to step back.

Next Week: We’re tackling another brutal truth that keeps clinicians up at night. See you then!

Until Next Week | The Underrated Superhero

© 2026 The Underrated Superhero LLC. All Rights Reserved.

📖 External Resources & Research

- 🔗 PMC: Dislikable Clients or Countertransference — Research on how clinicians experience and navigate dislike for clients, including coping strategies and impact on therapeutic alliance

- 🔗 APA: How to Manage Countertransference in Therapy — Evidence-based strategies for recognizing and working through emotional reactions to clients

- 🔗 Taylor & Francis: Countertransference Struggles of Mental Health Psychotherapists — Study on therapist experiences of guilt, shame, and difficult feelings toward clients

Previous Posts in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series

- 📖 My Client Hates Me: When Resistance Feels Personal

- 📖 I’m Making It Worse: Fear of Harming Clients

- 📖 I’m Too Tired to Care: Burnout and Compassion Fatigue

See all posts in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series