Therapist Attraction to Client

You’re six sessions in with a client who’s finally showing up consistently. They’re doing the homework. Making progress. You realize you’re actually looking forward to Thursdays.

And then one day you catch yourself thinking — wait, are they cute?

And then the panic. Am I a bad person? Is something wrong with me? Am I going to lose my license? What if someone finds out I even thought this?

Okay. Let’s just… slow down.

📚 This is Blog #16 in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series (Click to explore the series)

Weekly honest support for the struggles every clinician faces: “I hate group therapy.” “I can’t do this.” “My client hates me.” “I’m making it worse.” “I can’t say no.” “They’re going to report me.” “I’m too tired to care.” “What do I even say?” “I don’t know enough.” “They keep relapsing.” “Am I documenting wrong?” “My supervisor doesn’t get it.” “I can’t handle this caseload.” “Nobody told me about the paperwork.” “I don’t like my client.” “My client’s cute.”

These aren’t signs you’re failing. They’re signs you’re human.

This Is Going to Happen

You are going to have attractive clients. It’s not if. It’s when.

You’re a human being sitting across from other human beings for hours every week. Some of them are going to be good-looking. Some are going to be charming. Some are going to make you laugh. And some of them are going to start showing up differently as they get healthier — more confident, more put-together, more… yeah.

This doesn’t mean you’re broken. Doesn’t mean you’re going to act on it. Doesn’t mean you’re going to lose your license.

Research shows that around 87% of therapists report experiencing sexual attraction to a client at some point in their career. So, if you’re feeling like you’re the only one? You’re not. Not even close.

The Front Desk Sees Something Different

I remember this one time — young adult male client walked in for session and the three-admin staff up front started whispering. Blushing. Clearly thought he was cute.

And I just looked at them like… really?

Not because he wasn’t objectively attractive. He was. But I knew his stuff. I knew what he was working through, the chaos underneath, why he was in my office in the first place. They saw someone walk in put-together and confident. I saw the full picture — the work still ahead, the patterns we were trying to break, the stuff he was carrying.

That changes things. At least for me.

When you’re in the clinical role, you’re holding information that shifts how you see someone. You’re not just seeing the outside. You’re seeing the mess, the growth edges, the places they’re stuck. And for a lot of clinicians, I think, that full picture doesn’t exactly spark attraction. It sparks something else — care, investment, hope for their progress. But not attraction.

That said. Sometimes it does. And that’s where it gets complicated.

When It’s Not About Them — It’s About the Work

I had a client once who came in struggling with a lot. Suicidal ideation. Bad breakup. Trouble trusting anyone. The early sessions were heavy.

But then something shifted. He started following through on recommendations. Found employment. Was doing the work outside of session, not just showing up and venting. He opened up about past suicidal behavior — real vulnerability, real trust. And I got to watch him change.

That journey? I loved it. I was proud of him. I looked forward to our sessions.

And at some point I noticed — he’d become more attractive. Not because his face changed or anything. But because he was healthier. More confident. More alive.

That’s when I had to check myself.

I started doing this mental check-in before and after sessions. Like, why am I nervous right now? What am I actually feeling? Is this about him, or is this about the work?

And the answer, when I was honest, was always the work. I loved watching someone transform. I loved being part of that. But I had to keep separating that from anything personal. Because those two things — pride in their progress and attraction to them — can feel really similar if you’re not paying attention.

The Check-In You Need to Start Doing

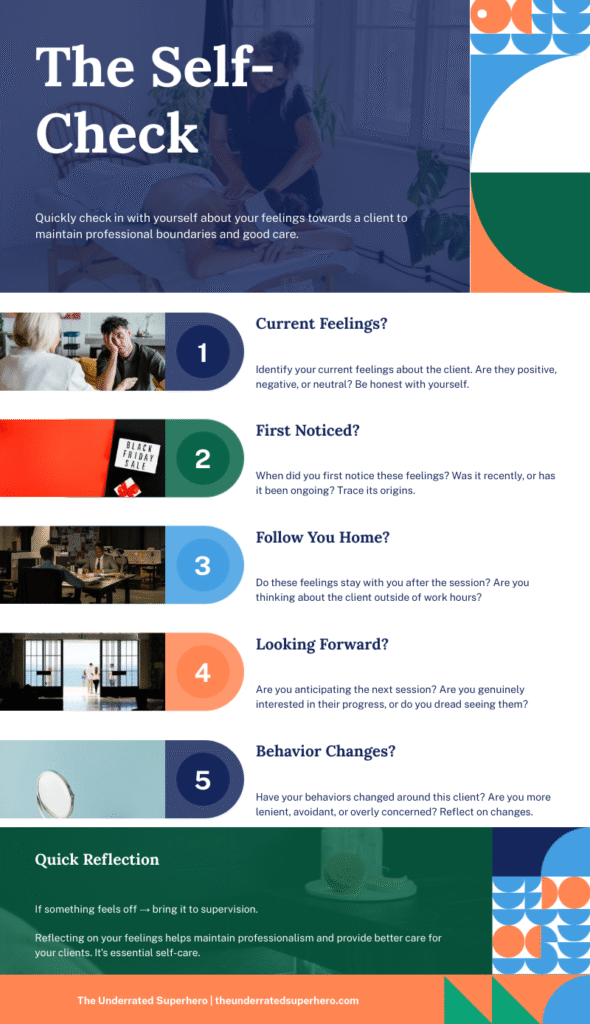

If you’ve got a client who makes you feel… something, here’s what I ask myself. You can do this in your head after session, journal it, bring it to supervision, whatever works.

- What specifically am I feeling about this client? Like, name it. Attraction? Pride? Excitement? Nervousness? Get specific.

- When did I first notice it? Was it immediate, or did it come on over time as they got better?

- Is this feeling present outside of session? Am I thinking about them at home? Or does it stay in the clinical space?

- Am I looking forward to seeing them or seeing their progress? This one’s the big one, I think. There’s a difference between “I can’t wait to see what they’ve worked on” and “I can’t wait to see them.”

- Have my behaviors changed? Am I dressing differently on days I see them? Extending sessions? Sending extra texts? Offering to reschedule less? These are subtle but they matter.

If you’re honest with yourself and everything points to “I’m invested in their progress” — you’re probably fine. Keep going.

If something feels off — if you’re thinking about them at home, if your behavior is shifting, if the feeling is about them specifically — that’s when you need to bring it somewhere.

Why Addiction Clients Are Higher Risk for This

Okay so let’s talk about the population for a second.

Clients in addiction treatment often come with really minimal support systems. They’ve burned bridges. They don’t trust easily. They’ve been let down by pretty much everyone.

So when they finally find someone who shows up consistently, who listens, who doesn’t judge — that can feel huge to them. They become grateful. Appreciative. Sometimes really intensely so.

And here’s the thing: a lot of these clients struggle with boundaries themselves. They might be suggestive. They might test limits. They might say things that feel like flirting because they honestly don’t know how else to connect. It’s not always predatory — they just don’t have a template for what a healthy professional relationship looks like.

Add in the fact that people in early recovery often go through this kind of “glow up” phase — sleeping better, eating better, taking care of themselves — and suddenly you’ve got a client who looks and acts completely different than when they first walked in.

This is why I think firm boundaries from day one matter so much. Not because you’re expecting something to go wrong. But because when someone starts testing, you’ve already established what this is and what it isn’t.

This connects to what I wrote about in I Can’t Say No — that struggle with holding limits when someone is pushing. With addiction clients especially, you need that foundation already in place.

What Firm Boundaries Actually Look Like

When I say “firm boundaries,” I don’t mean being cold or distant. I just mean being clear.

From the beginning, I make sure clients understand what my role is in their life. What I can do for them and what I can’t. I can support them clinically. I can help them build skills, process stuff, work toward their goals. I can’t be their friend. I can’t be their person outside of session. I can’t be anything other than their therapist.

I also make clear what’s respectful and what’s not. If something feels off in session — a comment, a look, whatever — I name it. Not in a punishing way, but in a “let’s talk about what just happened” way.

This protects them. And it protects you.

Because if you’ve already established the frame, then when something comes up — your feelings or theirs — you’ve got something to point back to. The boundary was always there. You’re just holding it.

The Guilt and Shame Are the Actual Problem

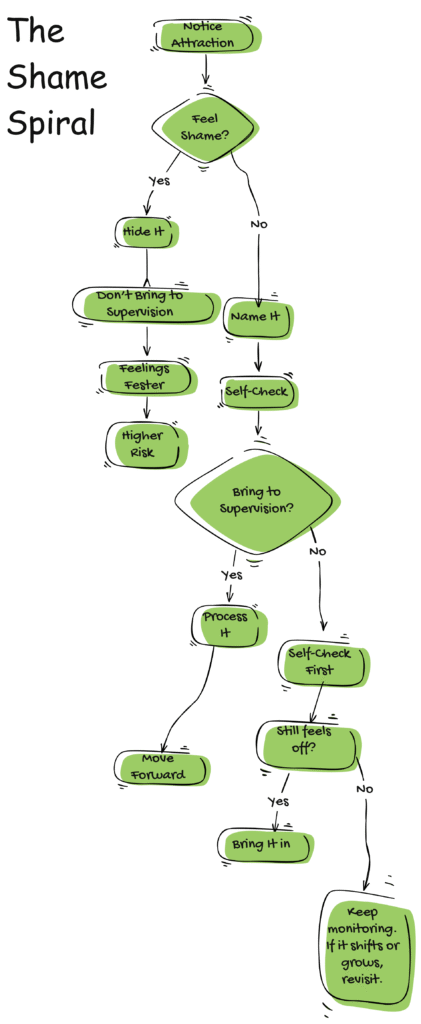

Here’s the thing I really want you to get: the feeling isn’t the danger. The shame about the feeling is.

When clinicians notice attraction and immediately spiral into “I’m disgusting, I shouldn’t be doing this work, something’s wrong with me” — that’s when things get risky. Because shame makes you hide. And hiding means you don’t bring it to supervision. You don’t process it. You just sit with it alone and it festers.

That silence? That’s actually where boundary violations start. Not with the initial thought. With the decision to bury it.

Modern approaches to countertransference actually view these feelings as information — something to notice, examine, and manage rather than something that makes you a bad therapist. The challenge is to use these feelings, not ignore them or suppress them.

If you can say to yourself, “okay, I noticed something, that’s human, let me think about what this means” — you’re already handling it. You’re doing what you’re supposed to do.

The clinicians who get into real trouble aren’t usually the ones who notice attraction and freak out about it. They’re the ones who convince themselves they’re the exception. Who tell themselves “this is different.” Who stop looking at their own behavior because they’re too ashamed to examine it.

Don’t be that person. Look at it. Name it. Figure out what to do.

When to Bring It to Supervision

Not every fleeting thought needs to go to your supervisor. If you notice a client is attractive and that’s the end of it — you don’t need to make some formal report about your own brain.

But here’s when you should bring it up:

You’re behaving differently. Longer sessions. Extra texts. Finding reasons to see them outside of appointments. Dressing differently. Any shift in your normal clinical behavior is a flag.

The client is pressing you. If they’re making comments, being suggestive, testing boundaries — and you’re not immediately redirecting — that’s when you need outside perspective.

You can’t shake it. If you’ve done the self-check, been honest with yourself, and the feeling is still there and growing — bring it in. That’s what supervision is for.

You’re avoiding the questions. If you find yourself not wanting to ask the hard questions, that’s probably the clearest sign you need to.

Supervision isn’t about getting in trouble. It’s about getting support. A good supervisor has seen this before. They’re not going to think you’re a monster. They’re going to help you figure out what’s next. If you need a framework for bringing this kind of stuff to supervision, the Supervision Prep Template in the Winter Survival Kit walks you through how to structure tough conversations with your supervisor.

Research on therapist attraction consistently shows that supervision and peer consultation are some of the most effective ways to work through these feelings in a healthy way. The therapists who don’t seek support? They’re the ones at higher risk.

What Happens If You Don’t Handle It

Okay, let’s talk about what’s actually at stake here. Because I think it’s worth being direct.

If a clinician acts on attraction to a client — whether that’s a relationship, something physical, or even just sustained boundary violations that blur the line — the consequences are serious.

Licensing board stuff. Depending on your state and what happened, you could face disciplinary action, suspension, losing your license entirely. This isn’t a warning. This is your career.

Getting fired. Most agencies have zero tolerance for this. You’re not getting a conversation. You’re getting walked out.

Harm to the client. And this is the one I don’t think people talk about enough. A client who came to you for help. Who trusted you. Who was vulnerable. You’ve now made their recovery about something else entirely. You’ve confirmed every fear they had about trusting people. You’ve set back their treatment, maybe permanently. You don’t get to undo that.

And here’s the part that’s harder to see — even if you never “act on it” in an obvious way, unchecked feelings lead to subtle stuff. You start making exceptions. You let things slide that you wouldn’t with other clients. You become less objective. The treatment suffers even if nothing technically “happens.”

That’s why the check-in matters. That’s why supervision matters. Not because you’re one thought away from disaster. But because small shifts, left alone, become bigger shifts. And by the time it’s obvious, it’s usually too late to fix it cleanly.

A Note on the Guilt

If you’re reading this and you’ve been beating yourself up already — take a breath.

Having a feeling doesn’t make you a predator. Noticing attraction doesn’t make you unsafe. The fact that you’re even reading this, thinking about it, worried enough to care — that’s actually a good sign. That’s someone who takes their role seriously.

The clinicians who cause harm aren’t usually the ones agonizing over it. They’re the ones who don’t look at it at all.

You’re doing the work by being willing to examine this. Keep doing that. And if you need support, ask for it.

The Self-Reflection Tool

Here’s what I’d want you to sit with whenever you notice something — attraction, nervousness, excitement, whatever feels like it needs examining. Journal through it or bring it to supervision. Whatever works for you.

What am I feeling about this client, specifically?

When did I first notice this feeling?

Is this feeling only during session, or does it follow me home?

Am I looking forward to seeing them, or seeing their progress?

Have any of my behaviors changed with this client? (Session length, how often I reach out, what I wear, how flexible I am with scheduling)

If a colleague told me this about their client, what would I say to them?

Is there something I’m avoiding looking at here?

Do I need to bring this to supervision?

You don’t have to answer all of every time. But if something feels off, start here.

Anyway

You’re capable of having attractive clients and maintaining good boundaries. I really believe that.

This isn’t some impossible standard. It’s a skill. Something you build by being honest with yourself, using your supports, and remembering why you’re in that room.

You’re there for them. Not the other way around.

And when you hold that — when you do the check-ins and stay connected to why you do this work — you can handle whatever feelings come up. Feelings aren’t actions. You get to decide what you do with them.

Next Week: We’re tackling another brutal truth that keeps clinicians up at night. See you then!

Until Next Week | The Underrated Superhero

© 2026 The Underrated Superhero LLC. All Rights Reserved.

📖 External Resources & Research

- 🔗 Pope et al: Sexual Attraction to Clients — Landmark research showing 87% of therapists experience attraction to clients, plus how they handle guilt, anxiety, and training gaps

- 🔗 APA: How to Manage Countertransference in Therapy — Evidence-based strategies for recognizing and working through emotional reactions to clients

- 🔗 PMC: Managing Transference and Countertransference in Supervision — Research on using supervision to process difficult feelings toward clients

Previous Posts in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series

- 📖 My Client Hates Me: When Resistance Feels Personal

- 📖 I’m Making It Worse: Fear of Harming Clients

- 📖 I’m Too Tired to Care: Burnout and Compassion Fatigue

- 📖 I Can’t Say No: When Boundaries Feel Impossible

- 📖 I Don’t Like My Client: When You Dread the Session

See all posts in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series