Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors

I agreed to write a letter overnight.

I didn’t finish it.

Instead of sending a message to explain the delay, I told myself I’d handle it tomorrow. Then tomorrow came and I still didn’t send it.

The client complained. Not just about the letter—about my therapy.

“You were so wonderful at first. And then you just… deteriorated.”

That word landed like a punch. Because part of me knew it was true.

Not that I was incompetent. But I was running on fumes. Forgetting things clients told me. Asking them to repeat information I should have remembered. Crying at home over a dead animal on the side of the road. Sobbing at random movie scenes. Then isolating to catch up on documentation I couldn’t finish during the day because I was constantly in sessions.

📚 This is Blog #7 in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series (Click to explore the series)

Weekly honest support for the struggles every clinician faces: “I hate group therapy.” “I can’t do this.” “My client hates me.” “I’m making it worse.” “I can’t say no.” “They’re going to report me.” “I’m too tired to care.”

These aren’t signs you’re failing. They’re signs you’re human.

I was working two full-time jobs—community mental health with adolescents and a full private practice caseload. Eighty-plus hours a week. My fibromyalgia was flaring. I wasn’t sleeping. Anxious. Depressed. Telling myself every single day: “I can’t do this.”

I kept showing up anyway. For three years.

What I didn’t understand then: I wasn’t failing. I was experiencing compassion fatigue.

If you’re reading this thinking “Maybe I’m just not cut out for this work,” stop. You’re not broken. Not incompetent. Exhausted in a way that’s invisible to everyone—including yourself.

This is about understanding what’s happening, why it happens to addiction counselors more than almost anyone else, and what actually helps. Not the generic self-care advice that feels insulting when you’re barely surviving. The real stuff.

What is Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors?

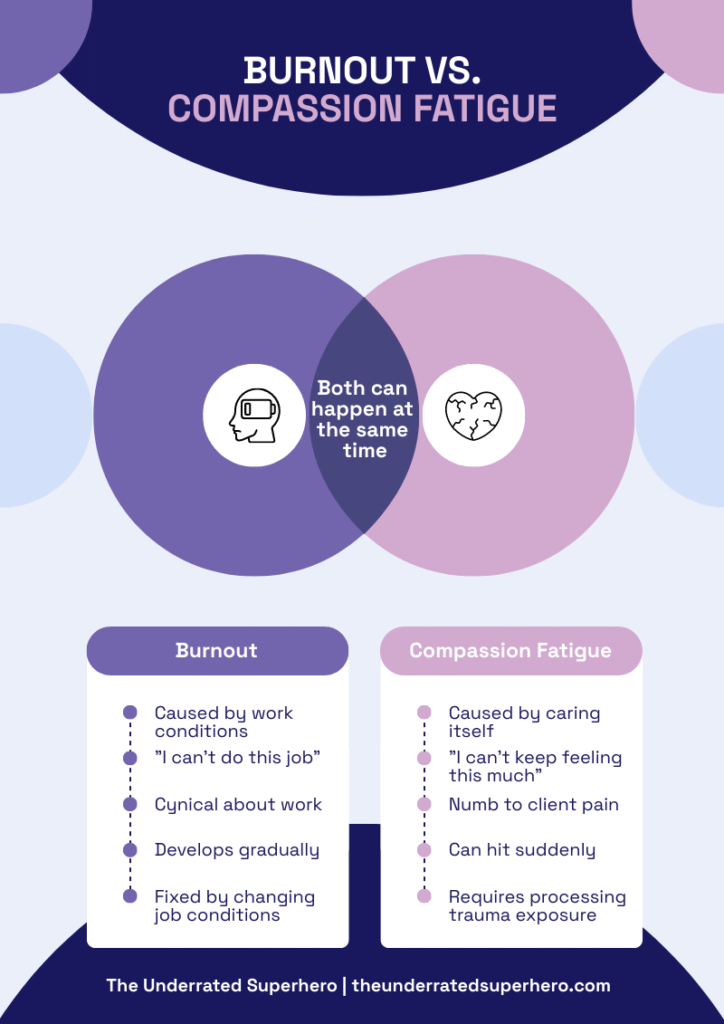

Most people think compassion fatigue and burnout are the same thing. They’re not.

Burnout happens when your job exhausts you. Too many clients, not enough resources, administrative bullshit, impossible caseloads. It’s about work conditions wearing you down. You feel cynical, detached, ineffective. You dread going to work.

Compassion fatigue is what happens when caring itself becomes unbearable. It’s the cost of absorbing other people’s trauma, pain, and suffering—especially when you can’t fix it. It’s not about hating your job. It’s about losing your capacity to feel empathy without it destroying you.

Here’s the key distinction:

- Burnout: “I can’t keep doing this job under these conditions.”

- Compassion fatigue: “I can’t keep feeling this much and survive.”

According to SAMHSA’s compassion fatigue research, addiction counselors experience some of the highest rates of compassion fatigue among helping professionals, with turnover rates exceeding 50% in some settings within the first two years.

Why Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors Is So Common

So why are addiction counselors at such high risk? Several factors converge to create the perfect storm for compassion fatigue.

Chronic exposure to trauma. Most clients with substance use disorders have trauma histories. You’re not just treating addiction—you’re holding space for abuse, violence, loss, systemic oppression, generational pain. Every intake is a trauma disclosure. Every relapse carries the weight of someone’s worst moments.

High stakes, limited control. Overdose is always possible. You can do everything right and your client can still die. That combination—life-or-death stakes with minimal control over outcomes—creates constant fear and helplessness.

Relapse is part of recovery (but it still hurts). Intellectually, you know relapse is common. Emotionally? Every time a client you care about uses again, it lands like failure. You replay sessions in your head. Wonder what you missed. Carry guilt that doesn’t belong to you.

Systemic failures you can’t fix. Your clients need housing, jobs, healthcare, childcare, transportation, trauma therapy, and about six months without a crisis. You can’t provide any of that. You watch people cycle through treatment because the system is broken, and you’re the one sitting with their despair.

Inadequate support and supervision. Many addiction treatment settings don’t prioritize clinical supervision, trauma-informed organizational practices, or reasonable caseloads. You’re expected to absorb crisis after crisis without processing it yourself.

The helper’s paradox. The qualities that make you good at this work—empathy, presence, commitment—are the same qualities that make you vulnerable to compassion fatigue. Your capacity to care deeply is both your greatest strength and your greatest risk.

Risk Factors for Compassion Fatigue in Addiction Counselors

You’re especially vulnerable if:

- You have personal or family history of addiction

- You work in under-resourced settings (community mental health, corrections, residential)

- You carry a high caseload (60+ clients is not sustainable, no matter what your employer says)

- You work with high-acuity populations (justice-involved, chronic relapse, co-occurring severe mental illness)

- You lack adequate clinical supervision or peer support

- You’re newer to the field

- You’re managing your own mental health challenges without adequate support

Look, if you’re reading this list thinking, “That’s literally all of me,” you’re not alone. These aren’t rare circumstances—they’re standard conditions for most addiction counselors.

Which is why compassion fatigue isn’t a personal failing. It’s a predictable response to an impossible situation.

Warning Signs of Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors

Self-Assessment: Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors Checklist

Check any symptoms you’ve experienced in the past month:

Your Score

Check the boxes above to see your results

Here’s the tricky part: Compassion fatigue doesn’t announce itself. There’s no moment where you wake up and think, ‘Ah yes, this is compassion fatigue.’ Instead, it creeps in slowly, disguised as normal stress or just ‘having a bad week. It creeps in slowly, disguised as normal stress or just “having a bad week.”

Here’s what it actually looks like:

Emotional Symptoms of Compassion Fatigue in Addiction Counselors

Numbness or emotional flatness. You’re sitting in session and your client is telling you something that should move you—but you feel nothing. Not bored. Not distracted. Just blank. Like you’re watching from behind glass.

Irritability and impatience. Small things set you off. A client shows up late and you’re furious. A colleague asks a simple question and you want to snap. You’re annoyed by things that never bothered you before.

Sudden, disproportionate emotions. You’re fine all day, then you see a dead animal on the side of the road and you’re sobbing. A sentimental commercial makes you cry. A minor mistake with your kids feels devastating. Your emotional responses don’t match the situation.

Dread before sessions. You used to look forward to certain clients. Now you look at your schedule and feel dread. Not because they’re difficult—just because you have to care again, and you’re not sure you have it in you.

Cynicism about recovery. You catch yourself thinking, “They’re just going to relapse anyway” or “Why am I even doing this?” You don’t want to think this way, but the thoughts show up anyway.

These emotional shifts often show up alongside physical symptoms you might be tempted to ignore.

Physical Signs of Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors

- -Chronic fatigue (even after sleeping)

- -Tension headaches or migraines

- -Stomach issues, digestive problems

- -Muscle pain, fibromyalgia flares

- -Insomnia or disrupted sleep

- -Getting sick more often

- -Increased reliance on caffeine, alcohol, or other substances to cope (and yeah, the irony isn’t lost on me)

As your body struggles, you’ll likely notice changes in your behavior too.

Behavioral Changes Linked to Compassion Fatigue

Avoidance. You start finding reasons not to see certain clients. You drag out your lunch break. You avoid opening client emails. You procrastinate on documentation because facing the work feels overwhelming.

Isolation. You stop talking to colleagues. You skip team meetings when you can. You go straight home and isolate instead of spending time with family or friends. You tell yourself you’re “just tired,” but really, you can’t handle one more person needing something from you.

Working more, accomplishing less. You’re at your desk for hours but not actually getting anything done. You stare at treatment plans. Reread notes without retaining anything. You’re present but not productive—and that makes the guilt worse.

Decreased self-care. You stop exercising. You eat like crap or forget to eat. You skip therapy appointments or supervision. The things that used to help feel like too much effort.

Cognitive Effects of Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors

Finally, compassion fatigue affects how you think and process information.

Difficulty concentrating. You’re in session and your client is talking, but you realize you haven’t heard the last two minutes. You ask them to repeat something they just told you. You forget important details about their treatment.

This was one of my warning signs. Clients would share something significant and the next session I’d have no memory of it. That’s when I knew—this wasn’t just being distracted. I was checked out.

Rumination and intrusive thoughts. You can’t stop thinking about clients when you’re off the clock. You replay sessions. Wonder if you said the right thing. Imagine worst-case scenarios. Your brain won’t shut off.

Impaired decision-making. Things that used to feel straightforward now feel impossible. Should I refer this client? Should I document this? You second-guess yourself constantly. Or worse—you stop caring about making good decisions because you’re too exhausted to think clearly.

What Causes Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors?

Understanding what causes compassion fatigue matters—not so you can blame yourself, but so you can recognize which factors are within your control and which are systemic failures you can’t fix alone.

1. The Helper’s Paradox

The qualities that make you good at this work are the same qualities that put you at risk.

- Empathy allows you to connect with clients and understand their pain. But here’s the cost: It also means you absorb that pain—session after session, day after day—without a way to discharge it.

- Commitment keeps you showing up for clients even when it’s hard. It also makes it nearly impossible to set limits or walk away when you should.

- Competence means you can handle complex cases and high caseloads. It also means your employer keeps adding more—because you can handle it, so why wouldn’t they?

This is the paradox: The better you are at your job, the more vulnerable you become to compassion fatigue.

You care deeply. You show up fully. You take your work seriously. And the system exploits that until you break.

2. Boundaries (But Not the Way You Think)

Beyond the paradox of your strengths becoming vulnerabilities, there’s another layer to this. Compassion fatigue is not caused by “poor boundaries.”

I wrote an entire blog about this, but the short version: when you’re working in an under-resourced, underpaid system with impossible caseloads and inadequate support, the problem isn’t that you “can’t say no.” The problem is the system itself. It’s designed to extract maximum labor from clinicians who care too much to let clients suffer.

That said, there are boundary issues that contribute:

Emotional over-responsibility. You believe it’s your job to fix your clients’ lives. When they struggle, you feel like you failed. When they relapse, you replay every session wondering what you missed. You carry responsibility that doesn’t belong to you.

Inability to metabolize trauma exposure. You hear traumatic disclosures all day and have nowhere to process it. No supervision. No debriefing. You just absorb it and move on to the next client. That’s not a boundary problem—that’s system failure. But recognizing it can help you advocate for what you need.

Working off the clock (because you have to). You’re answering crisis calls at 9 PM. Finishing documentation at home because your entire workday was spent in sessions. Thinking about clients during dinner because you never had time to decompress. This isn’t poor boundaries. This is exploitation. But it accelerates compassion fatigue.

3. System Failures

But individual factors only tell part of the story. The bigger issue? The systems themselves. Most compassion fatigue isn’t caused by individual clinicians doing something wrong. It’s caused by systems that treat clinicians as expendable.

Unsustainable caseloads. You’re managing 60, 80, 100+ clients. That’s not clinically sound. That’s not evidence based. That’s just what the funding allows—and you’re the one paying the cost. Research consistently shows that caseloads above 40-50 clients compromise care quality, yet many addiction treatment settings operate with counselors managing 80-100+ clients due to funding constraints and workforce shortages.

Inadequate supervision and support. Many addiction treatment settings don’t provide regular clinical supervision. Meanwhile, you’re expected to navigate complex trauma, high-risk clients, and ethical dilemmas without guidance or processing time.

Chronic under-resourcing. Your clients need stable housing, trauma therapy, medical care, transportation, childcare, financial support. You can’t provide any of that. You watch people cycle through treatment because they don’t have the basic resources to stabilize—and you’re the one sitting with their despair.

Lack of organizational trauma-informed practices. The same agencies that tell clients to practice self-care don’t offer staff paid time off, mental health days, or trauma-informed supervision. The hypocrisy is exhausting.

Low pay, high expectations. You’re doing life-or-death work for wages that don’t cover rent. You’re told you’re “making a difference” while being chronically underpaid and overworked. That disconnect between the value of your work and how you’re compensated creates resentment and burnout.

4. Cumulative Grief: A Hidden Cause of Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors

This one doesn’t get talked about enough. Underneath all of these factors lies something most people never talk about.

- Every client you lose to overdose is a loss.

- Every client who disappears and you never know what happened.

- Every client who gets re-incarcerated.

- Every client whose trauma you couldn’t fix.

- Every client who needed more than you could give.

Worse yet, you don’t get time to grieve these losses. There’s no funeral. No closure. No acknowledgment that you just lost someone you cared about—because there are 15 more clients on your schedule today, and they need you to show up.

Cumulative grief is what happens when you experience loss after loss without processing it. It builds. It hardens. Eventually, it shuts you down—because feeling the grief is too painful, so you stop feeling anything at all.

That numbness? That’s not apathy. That’s self-protection.

The Bottom Line

So when you put it all together, compassion fatigue happens when:

- You care deeply about work that exposes you to chronic trauma

- You work in systems that exploit your empathy and competence

- You absorb grief and pain without time or space to process it

- You lack adequate supervision, support, and resources

- You’re expected to do the impossible—and then blamed when you can’t

This is not your fault.

But it is your reality. And understanding the causes is the first step toward recovery.

Recovery Strategies: Overcoming Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors

Most advice about recovering from compassion fatigue is useless.

- “Practice self-care!” (While working 80 hours a week?)

- “Set better boundaries!” (While managing an impossible caseload?)

- “Just take a vacation!” (With what money and time off?)

Here’s what actually works—organized by what you can do this week, what needs to happen this month, and what you need to build long-term.

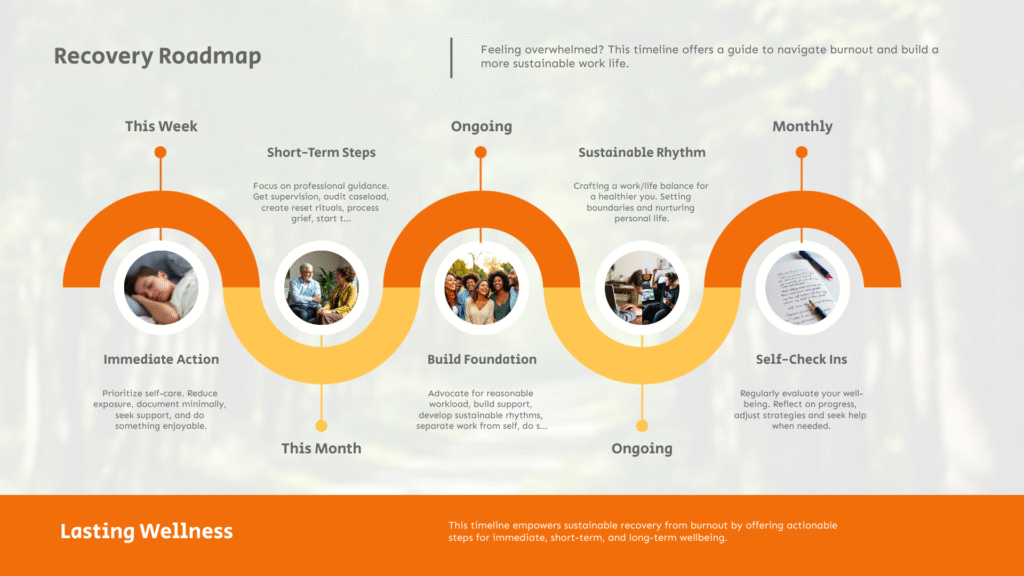

Immediate Interventions for Compassion Fatigue in Addiction Counselors (This Week)

Small, achievable actions you can take right now—even if you’re barely functioning.

1. Name what’s happening. Say it out loud: “I’m experiencing compassion fatigue.” Tell a trusted colleague, your supervisor, your therapist, your partner. Naming it makes it real—and makes it something you can address instead of something you’re secretly failing at.

2. Reduce your exposure (even slightly).

- Can you reschedule one high-intensity client this week?

- Can you skip one optional meeting?

- Can you take 10 minutes between sessions to sit in your car and breathe?

- Can you turn off work notifications on your phone after 6 PM?

You don’t have to fix everything this week. You just need to create one small pocket of relief.

3. Stop the bleeding on documentation. If you’re drowning in notes, do this: write the bare minimum required to be compliant and ethical. This is not the time for beautifully crafted treatment plans. Get it done. Move on.

If you’re drowning in notes, tools like the Quick Capture Progress Note System can help you document efficiently without spending hours on each note.

4. Tell someone you’re struggling. Not “I’m fine, just busy”—actually tell someone. A supervisor. A colleague. A friend. Ask for help with something specific: “Can you cover my phone for an hour?” “Can you review this safety plan with me?” “Can I just vent for five minutes?”

5. Do one thing that feels good. Not “self-care” in the Instagram sense. Just one thing that doesn’t hurt. A walk. A nap. A meal you actually enjoy. A show that makes you laugh. Permission to do nothing for 20 minutes.

Once you’ve created some breathing room with these immediate interventions, you’re ready for the next phase.

Short-Term Recovery from Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors (This Month)

Once you’ve stopped the immediate bleeding, these are the next steps.

1. Get real supervision.

If you don’t have regular clinical supervision, find it. Pay for it if you have to. Join a peer consultation group. Find a mentor. You need space to process what you’re holding—and you can’t do that alone.

2. Audit your caseload.

Look at your current clients and ask:

- Which clients drain me the most?

- Are there clients I could transfer or discharge appropriately?

- Are there clients I’m holding onto out of guilt rather than clinical necessity?

You don’t have to discharge everyone who’s hard. But if you’re carrying 80+ clients and half of them don’t need weekly sessions, something has to give.

3. Create a post-session reset ritual.

You need a buffer between sessions—something that allows you to discharge the emotional weight before you see the next person.

Examples:

- -Stand up, shake your body, take three deep breaths

- -Step outside for 60 seconds

- -Write one sentence about what happened, then close the note

- -Listen to a specific song that resets your nervous system

It doesn’t have to be elaborate. It just has to be consistent.

4. Process cumulative grief.

You need to acknowledge the losses you’ve been carrying.

- -Write down the names of clients you’ve lost (to overdose, incarceration, disappearance)

- -Say their names out loud

- -Acknowledge that you cared about them and their deaths/struggles matter

- -Give yourself permission to grieve

This might sound too simple, but naming loss is powerful. You can’t process what you won’t acknowledge.

5. Start therapy (or restart it).

If you’re a therapist who isn’t in therapy, this is your sign. You need your own space to process—not just “clinical supervision” where you talk about cases, but actual therapy where you process your own stuff.

If you can’t afford therapy, look for:

- Employee Assistance Programs (EAP)

- Sliding scale therapists

- Community mental health clinics

- Peer support groups

Now that you’ve addressed the crisis and started building sustainable habits, here’s what protects you over time.

Long-Term Prevention: Sustaining Recovery from Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors

These are the practices that will protect you over time—but they require systemic change, not just individual effort.

1. Advocate for reasonable caseloads.

You cannot prevent compassion fatigue if you’re managing 80+ clients. That’s not sustainable. Period. If your organization won’t reduce caseloads, document the impact:

- Track how many clients you see per week

- Note when you can’t provide adequate care due to volume

- Bring data to supervision or leadership

Sometimes the answer is: this job is not survivable. But sometimes, advocacy works.

2. Build a professional support network.

You need colleagues who get it. People you can text when a client dies. People who understand why you’re crying in your car after a session. People who won’t tell you to “just practice self-care.”

Join a consultation group. Find a mentor. Connect with other addiction counselors online. You can’t do this work in isolation.

3. Develop a sustainable work rhythm.

What does “sustainable” actually look like for you?

- How many high-acuity clients can you see in a week before you’re toast?

- How much time do you need between sessions?

- What’s your maximum number of sessions per day before quality declines?

Once you know your limits, protect them. Schedule breaks. Block off time for documentation. Say no to “just one more client” when you’re already maxed out.

4. Separate your identity from your work.

You are not your job. Your worth is not determined by how many clients you save. You are allowed to leave work at work.

This is hard—especially if you’re driven by purpose and meaning. But if your entire identity is wrapped up in being a helper, you will burn out. Cultivate other parts of yourself.

5. Revisit this regularly.

Compassion fatigue isn’t a one-time problem you solve. It’s an occupational hazard that requires ongoing attention. Check in with yourself monthly:

- Am I still feeling present in sessions?

- Am I sleeping okay?

- Am I dreading work more than usual?

- Am I isolating or avoiding people?

Catch it early, before it becomes a crisis.

Compassion Fatigue Myths and Mistakes Addiction Counselors Should Avoid

There’s a lot of terrible advice out there. Let’s clear up what doesn’t work.

Myth #1: “Just practice more self-care”

Self-care can be part of recovery—but only if the conditions causing compassion fatigue are also addressed. Otherwise, it’s just a band-aid on a hemorrhage.

Focus on harm reduction for yourself. What’s the smallest thing that actually gives you relief? Do that. But don’t let anyone tell you that compassion fatigue is your fault for not taking enough bubble baths.

Myth #2: “You just need better boundaries”

As I wrote in my previous blog about boundaries, framing compassion fatigue as a “boundary problem” is victim-blaming language. It implies that if you were just better at saying no, you wouldn’t be struggling.

The reality? You’re working in a system designed to exploit your empathy. You’re expected to do impossible work with inadequate resources. That’s not a boundary issue—that’s exploitation.

Yes, there are moments where you can set limits—not answering texts at 10 PM, transferring clients when appropriate. But the bigger work is recognizing when the system is the problem. Then either advocate for change or recognize it’s time to leave.

Myth #3: “Take a vacation and you’ll feel better”

Sure, a vacation gives you temporary relief. However, if you’re returning to the same impossible conditions. But if you’re returning to the same impossible conditions, you’ll be back in crisis within two weeks.

Also, many addiction counselors can’t afford vacations. And even when they can, they spend the entire time dreading their return to work.

If you can take time off, do it. But use that time to get clarity: Is this job survivable with changes? Or is it time to leave? A vacation won’t fix structural problems.

Myth #4: “You’re just not cut out for this work”

Compassion fatigue is not a sign of weakness or incompetence. It’s a predictable response to chronic trauma exposure in under-resourced systems.

If you’re experiencing compassion fatigue, it means you care. It means you’re good at this work. It means you’ve been absorbing pain without adequate support—not that you’re failing.

Stop questioning whether you’re “cut out” for this. Start questioning whether the conditions you’re working under are survivable. Two very different questions.

Myth #5: “You should be able to leave work at work”

This advice assumes you’re working a job with clear boundaries, predictable hours, and manageable stakes. Addiction counseling is not that job.

You’re doing life-or-death work. You’re holding space for trauma. You’re watching people you care about struggle. Of course it follows you home. That’s not a personal failing—it’s the nature of the work.

Instead of trying to “leave work at work” (which is unrealistic), focus on creating rituals that help you transition. A post-work decompression routine. Supervision where you actually process cases. Space to acknowledge that this work is hard—and it’s okay that it affects you.

Common Mistakes That Make It Worse

Beyond these widespread myths, here are specific mistakes that deepen compassion fatigue—even when you’re trying to recover.

Isolating instead of connecting. When you’re exhausted, it’s tempting to withdraw. But isolation makes compassion fatigue worse. You need connection—even if it’s just texting a colleague, “Today was brutal.”

Using substances to cope. Drinking to unwind. Using weed to sleep. Relying on stimulants to get through the day. This might provide short-term relief, but it compounds the problem long-term. (And yes, I know the irony of addiction counselors using substances to cope. That’s part of why this work is so hard.)

Ignoring physical symptoms. Your body is telling you something. If you’re getting migraines, stomach issues, chronic pain, insomnia—that’s not “just stress.” That’s your body shutting down. Don’t wait until you collapse to take it seriously.

Staying in toxic work environments out of loyalty. You feel guilty leaving because your clients need you. Your coworkers need you. The organization is understaffed. But staying in a job that’s destroying you doesn’t help anyone—including your clients.

Trying to “push through.” You tell yourself, “I just need to get through this week / this month / until this crisis passes.” But there’s always another crisis. Compassion fatigue doesn’t resolve by ignoring it. It gets worse.

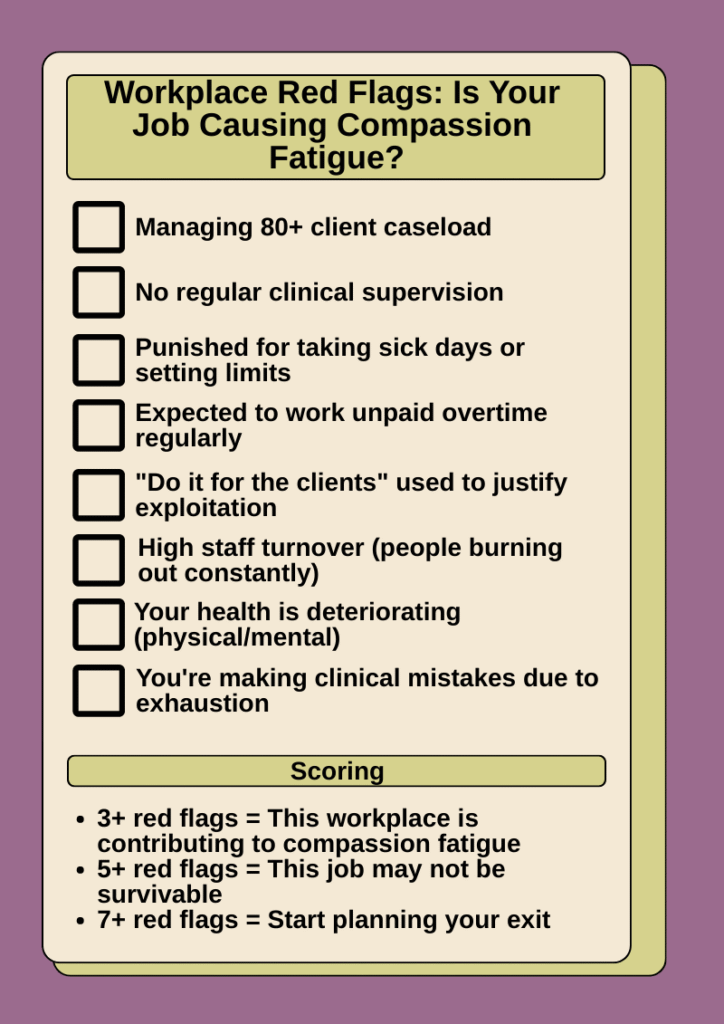

When Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors Means It’s Time to Leave

Nobody tells you this when you enter the field: Sometimes the most ethical thing you can do is leave.

Not every job is survivable. Not every organization can be fixed. And staying in a position that’s destroying you doesn’t help your clients—it just ensures that eventually, you’ll leave the field entirely.

Red Flags That Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors Is a Workplace Issue

Compassion fatigue can happen anywhere—but some workplaces actively create the conditions that guarantee it. Here are the signs that your job is the issue, not you:

1. Your caseload is clinically unsound.

If you’re managing 80+ clients, seeing 10+ people per day, or expected to provide quality care without adequate time for documentation or case management—that’s not sustainable. No amount of “time management” will fix it.

2. There’s no real supervision or support.

You’re navigating complex trauma, high-risk clients, and ethical dilemmas without regular clinical supervision. Or worse, “supervision” is just your boss asking if your notes are done.

3. You’re punished for setting boundaries.

When you try to take a sick day, reduce your caseload, or ask for help, you’re met with guilt, passive aggression, or threats to your job security.

4. The organization exploits your empathy.

They rely on your commitment to clients to keep you working unpaid overtime, covering for understaffing, and absorbing impossible conditions. “Do it for the clients” becomes the excuse for exploitation.

5. There’s no path to change.

You’ve advocated for better conditions. You’ve brought data to leadership. You’ve proposed solutions. Nothing changes. The organization is not interested in protecting staff—only in maximizing billable hours.

6. Your physical or mental health is deteriorating.

You’re getting sick constantly. You’re on anxiety or depression medication for the first time. You’re having panic attacks. You’re using substances to cope. Your relationships are suffering. You’re not sleeping.

If your job is making you physically or mentally ill, it’s time to leave.

7. You’re providing substandard care—and you know it.

You’re forgetting important details. You’re making clinical mistakes. You’re not fully present in sessions. You’re avoiding clients. You know you’re not doing your best work—not because you’re incompetent, but because you’re too depleted to function.

When you can no longer provide ethical care, staying is not noble. It’s harmful.

For more guidance on recognizing toxic workplace patterns and advocating for change, The National Council for Mental Wellbeing’s workforce wellness resources provide frameworks for assessing organizational health and worker safety.

Permission to Leave Toxic Environments

If you’re checking off multiple red flags, here’s what you need to hear:

You are allowed to leave.

You’re allowed to leave even if:

- Your clients need you

- Your coworkers are overwhelmed

- The organization is understaffed

- You feel guilty

- You don’t have another job lined up

- You worked so hard to get this position

- People tell you you’re “abandoning” clients

You cannot help anyone if you’re collapsing.

Leaving a toxic job is not failure. It’s not selfishness. It’s not weakness. It’s survival.

And here’s the truth: when you leave, the organization will replace you. They’ll hire someone else, burn them out, and replace them too. That cycle will continue until the organization changes its practices—or until it runs out of people willing to accept those conditions.

You staying doesn’t fix the system. It just ensures you’re the next casualty.

Questions to Ask Yourself

Still not sure if it’s time to leave. Ask yourself these questions:

1. Can this job be fixed with changes?

- If you had reasonable supervision, would this be sustainable?

- If your caseload were reduced, could you do this work safely?

- Are the problems structural (fixable) or cultural (probably not)?

2. Have I advocated for what I need?

- Have I clearly asked for supervision, reduced caseload, or support?

- Has leadership responded with action, or just empty promises?

- Am I staying because I believe it will get better, or because I’m too exhausted to leave?

3. What would I tell a client in my situation? If a client told you they were in a job that was destroying their mental health, giving them panic attacks, and making them physically ill—what would you tell them?

Now take your own advice.

4. What’s the cost of staying vs. leaving?

- If I stay: What will this cost me in health, relationships, quality of life?

- If I leave: What will this cost me financially, professionally?

- Which cost is actually bearable?

5. Am I staying out of commitment or out of fear?

- Am I staying because this work matters to me and the conditions are survivable?

- Or am I staying because I’m afraid I won’t find another job, won’t be able to pay bills, or will let people down?

Fear is not a good enough reason to destroy yourself.

6. If I left, what would I do? You don’t need a perfect plan. But if you can’t even imagine what leaving would look like, that’s a sign you’ve been in survival mode too long. Give yourself permission to think about it.

What Leaving Can Look Like

Leaving doesn’t have to mean leaving the field entirely. Though that’s okay too. There are many ways to step back:

- Transferring to a different program within your organization

- Moving to a setting with lower acuity (outpatient instead of residential, individual practice instead of agency)

- Reducing to part-time while you recover

- Taking a temporary leave of absence

- Shifting to a related role (training, consultation, supervision)

- Leaving clinical work to focus on education, advocacy, or administration

You can love this work and still need to step back.

A Final Word on Leaving

I stayed in a job that was destroying me for three years. I told myself I couldn’t leave—because of tuition reimbursement, because of vesting, because I loved my clients, because I thought I could handle it.

I was wrong.

I should have left sooner. Not because the work wasn’t important—but because staying as long as I did cost me my health, my relationships, and nearly cost me my career.

If you’re reading this and thinking, “I should leave, but I can’t yet,” I hear you. Sometimes the timing isn’t right. But please don’t confuse “not yet” with “never.”

Start planning your exit. Even if you don’t use it, having a plan gives you agency.

And if you do leave? You’re not giving up. You’re making space for the next version of your career—one that doesn’t require you to sacrifice your wellbeing to do meaningful work.

Recovering from Compassion Fatigue for Addiction Counselors: You’re Not Broken

If you’ve made it this far, I want you to know: You’re not failing. You’re surviving.

Compassion fatigue isn’t a character flaw. It’s not a sign you chose the wrong career. It’s not proof that you’re “too sensitive” or “not cut out for this work.”

It’s a predictable response to doing deeply human work in systems that were never designed to support the people doing it.

You care about your clients. You show up even when it’s hard. You carry more than most people could imagine. That empathy, that commitment, that competence—those are your greatest strengths.

But they’re also what makes you vulnerable.

But here’s the good news: Recovery is possible. The catch? It requires you to stop blaming yourself and start making changes—some small, some significant.

What to Do This Week

You don’t have to fix everything right now. Just start here:

- Name what’s happening. Say it out loud: “I’m experiencing compassion fatigue.”

- Tell someone. A colleague, supervisor, therapist, friend. Ask for one specific form of help.

- Create one small boundary. Turn off work notifications after 6 PM. Reschedule one session. Take 10 minutes between clients to breathe.

- Do one thing that feels good. Not Instagram self-care. Just something that doesn’t hurt.

What to Do This Month

Once you’ve taken those first steps, build on that momentum:

- Get real supervision. If you don’t have it, find it. Pay for it. Join a peer group. You need space to process what you’re holding.

- Audit your caseload. Are there clients you’re holding onto out of guilt? Can anyone be appropriately transferred or discharged?

- Process your grief. Write down the names of clients you’ve lost. Say them out loud. Give yourself permission to grieve.

- Start (or restart) therapy. You need your own space to process—not just supervision, but actual therapy for you.

What to Do Long-Term

As you stabilize, focus on what keeps you sustainable:

- Advocate for reasonable conditions. Document your caseload. Bring data to leadership. If nothing changes, start planning your exit.

- Build a support network. Find colleagues who get it. Join consultation groups. Connect with other addiction counselors.

- Separate your identity from your work. You are not your job. Your worth is not determined by how many clients you save.

- Revisit this regularly. Compassion fatigue isn’t a one-time problem. Check in with yourself monthly. Catch it early.

Resources to Help You

If you’re struggling with compassion fatigue, here are some tools that can help:

- Free Compassion Fatigue Self-Assessment – A downloadable worksheet to track your symptoms and recognize patterns

- New Clinician Survival Kit – Quarterly resources designed specifically for counselors navigating the first years of this work (includes boundary-setting tools, clinical confidence planners, and supervision prep checklists)

- SAMHSA’s Guide to Compassion Fatigue – Evidence-based strategies for recovery

- The National Council for Mental Wellbeing – Workplace wellness resources for behavioral health professionals

You Don’t Have to Do This Alone

And if you’re a new clinician trying to survive your first year (or your tenth year that feels like your first), check out the New Clinician Survival Kit—a quarterly resource designed to give you the tools, confidence, and community you need to make it through.

Learn more about the Survival Kit →

Final Thought

You became an addiction counselor because you wanted to help people. You wanted to make a difference. You wanted to do work that mattered.

You’re still doing that work. Even on the days when it doesn’t feel like it.

Compassion fatigue doesn’t mean you’ve stopped caring. It means you’ve been caring without adequate support for too long.

Give yourself the same compassion you give your clients. Acknowledge what you’re carrying. Ask for help. Make changes, even small ones. And if you need to leave, give yourself permission.

You deserve to do work that matters without it destroying you.

So remember this: You’re not broken. You’re not failing.

You’re just exhausted.

And that’s something we can work with.

Next Week: We’re tackling another brutal truth that keeps clinicians up at night. See you then!

Until Next Week | The Underrated Superhero

© 2025 The Underrated Superhero LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Resources Referenced in This Post

- SAMHSA’s Guide to Compassion Fatigue – Evidence-based strategies for recognizing, preventing, and recovering from compassion fatigue in behavioral health professionals

https://www.samhsa.gov/dtac/recovering-disasters/preparedness - The National Council for Mental Wellbeing – Workplace wellness resources, trauma-informed organizational practices, and support for behavioral health professionals

https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/ - Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) – Free assessment tool to measure compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress

https://proqol.org/ - Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): Behavioral Health Workforce – Resources on supporting addiction counselors, workforce development, and addressing systemic challenges in SUD treatment

https://www.samhsa.gov/behavioral-health-workforce

Additional Support from The Underrated Superhero

- 📚 Quick Capture Progress Note System – Streamline documentation so you can spend less time on notes and more time recovering between sessions

- 🛠️ New Clinician Survival Kit – Quarterly tools including 90-Day Confidence Planner, Supervision Prep Checklists, and frameworks for managing overwhelming caseloads

- 📝 Free Clinical Tools – Download the Compassion Fatigue Self-Assessment and other resources to help you recognize and address burnout early. Requires free account.

- 📧 Subscribe to the New Clinician Survival Kit Series – Weekly honest support for the struggles every clinician faces—no fluff, no toxic positivity, just real talk

Previous posts in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series:

Week 1: I Hate Group Therapy: How I Went from Dreading sessions to Loving Them

Week 2: I Can’t Do This: When Imposter Syndrome for Therapists Hits Hardest

Week 3: My Client Hates Me: When Resistance Feels Personal

Week 4: I’m Making It Worse: Fear of Harming Clients

Week 5: I Can’t Say No: Setting Boundaries with Clients

Week 6: They’re Going to Report Me: Professional Fear & Compliance Anxiety