Blog #4 in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series (“Making Clients Worse“)

The stories in this post are real, messy, and uncomfortable—because that’s what early clinical work actually feels like. I’m sharing my mistakes and uncertainties not because I’m seeking absolution, but because someone else sitting in their car after a disaster session needs to know they’re not the only one. If you’re reading this and exhaling with relief because someone finally said it—welcome. You’re in the right place.

They didn’t come back.

You replay the first session in your head—what did you say? What did you miss? Did you push too hard? Not hard enough? Were you the therapist who turned them off from therapy altogether?

This is the thought that keeps me up at night, even now. Especially in private practice, where there’s no supervisor to tell you “they moved” or “their insurance changed” or some other rational explanation that has nothing to do with your competence. You’re just left with silence and the terrible possibility that you became someone’s cautionary tale. The therapist they’ll mention years from now when explaining why they’re hesitant to try again.

I’ve heard horror stories from clients about their previous therapists. The ones who said the wrong thing, pushed too hard, didn’t understand them. And every time I hear those stories, I think: What if I’m someone’s next horror story?

If you’ve ever sat with the fear that you’re making a client’s situation worse, you’re not paranoid. This fear is something nobody prepared you for. These fears are part of the new clinician survival journey—and having the right resources makes all the difference.

📚 New Clinician Survival Kit Series: Weekly Support for Your Clinical Journey (Click to explore)

An Ongoing Journey: Weekly honest support for the struggles every clinician faces—from survival to specialization

“I hate group therapy.” “I can’t do this.” “My client hates me.” “I’m making it worse.”

These aren’t signs you’re failing. They’re signs you’re human. This ongoing series tackles the brutal honesty of clinical work—whether you’re barely surviving your first year or ready to refine your practice and specialize.

New posts every Saturday. Real struggles. Practical tools. Genuine understanding from someone who’s been there.

This Series Grows With You

Whether you’re drowning in doubt or ready to level up your practice, there’s a blog (and resources) for where you are right now.

- Some topics get comprehensive resource hubs—complete with multiple posts, forums, tools, and products

- Others are standalone posts with everything you need built right in

And here’s the complicated part: sometimes you’re not making clients worse at all. Sometimes the system is failing both of you. And sometimes—I don’t know, maybe not as rarely as we’d like to think—you actually are the problem.

When It Feels Like You’re Making Clients Worse (But You’re Not)

The Art Project Disaster

I showed up to facilitate an art therapy group with everything except the paper and paint.

I had paintbrushes. Glue. Colored pencils. Plates, cups, every peripheral supply you could imagine. But not the two things that actually mattered. The kids were so disappointed. I was mortified. I apologized and tried to pivot to something else—probably a psychodrama activity on the board—but the group never recovered. You could feel how fragmented it was from the start.

Side conversations between clients. Visible disinterest. I’d give a prompt and get nothing. Multiple redirects just to get minimal participation. Shrugging. Silence. Nobody making eye contact. All the signs that whatever you’re doing isn’t landing.

I suck at this. This isn’t working. I’m not cut out for this.

That’s what runs through your head when a group goes sideways. Not the clinical explanation about group dynamics or the rational acknowledgment that one bad session doesn’t define your competence. Just the raw conviction that you’re failing everyone in the room.

When the System Fails You Both

In the beginning of group, I asked the art teachers if they could spare any materials. They said no—it comes out of their pocket too. Which, welcome to school-based work, where you learn very quickly that systemic failures will consistently make you question whether you’re adequate as a clinician.

School-based mental health professionals face unique systemic barriers, including inadequate funding and lack of administrative support. I brought in stuff for a few parties each year. I tried to be creative and resourceful with basically nothing. And I still felt like I was making it worse—like I was making these clients worse by not being able to provide what they actually needed. Like these kids deserved so much more than just a poor substance abuse counselor who could barely afford the basics, let alone the materials that might actually help.

A team of professionals working on prevention and treatment? That’s too aspirational. They got me, printed handouts, and whatever I could scrape together.

I internalized that. Hard.

Looking Back Now

Looking back now, I don’t know. Those kids didn’t need a therapist with unlimited resources. They needed a system that didn’t force clinicians to choose between adequate materials and paying their own bills. But in the moment? In the moment it just felt like I was the one falling short.

When a group feels disorganized, when activities fall flat, when you forget something important—your first instinct will be to assume you’re the problem. And maybe sometimes you need to look at what you’re working with before you decide you’re the one failing.

But I’m still not totally sure how to do that.

When Family Sessions Feel Like They’re Falling Apart

The Impossible Tightrope Walk

Then there are the family sessions that make you question everything.

You’re trying to advocate for your client—a teen who’s struggling but deserves space and boundaries—while their parents are understandably worried and pushing for consequences you know won’t help. Maybe the kid’s using substances and the parents want harsher punishment or a higher level of care. You’re doing this impossible tightrope walk: validating the parents’ very real concerns while trying to explain adolescent development, explaining that this behavior isn’t necessarily abnormal, trying to keep everyone in the room long enough to actually help.

It’s exhausting. And I’m not always sure I’m doing it right.

When You Sense the Disengagement Coming

Some sessions feel productive to me, but I can sense the disengagement coming. Parents getting up repeatedly. Canceling appointments. The shift from “this is hard but we’re working through it” to “we’re done here” is obvious, and you’re left wondering what you did wrong.

Other times, the session turns into the parent using your presence as an opportunity to tell their kid they’re bad. To list everything wrong with them. To make it clear how much “help” they need just to be tolerable. That’s not therapeutic. That’s harmful. And you’re sitting there wondering if you’re making clients worse by bringing everyone together in the first place.

Therapeutic ruptures in family therapy aren’t negative—they are actually opportunities for growth. But that doesn’t make them feel any less like disaster in the moment. I’ve had parents buckle down and say, “I don’t want you to see my kid anymore” or “I’m going to find someone else.” And that’s their right. But it doesn’t stop you from wondering if you pushed too hard, or not hard enough, or said the wrong thing, or—

A Tool for When Family Sessions Feel Like You’re Making Clients Worse

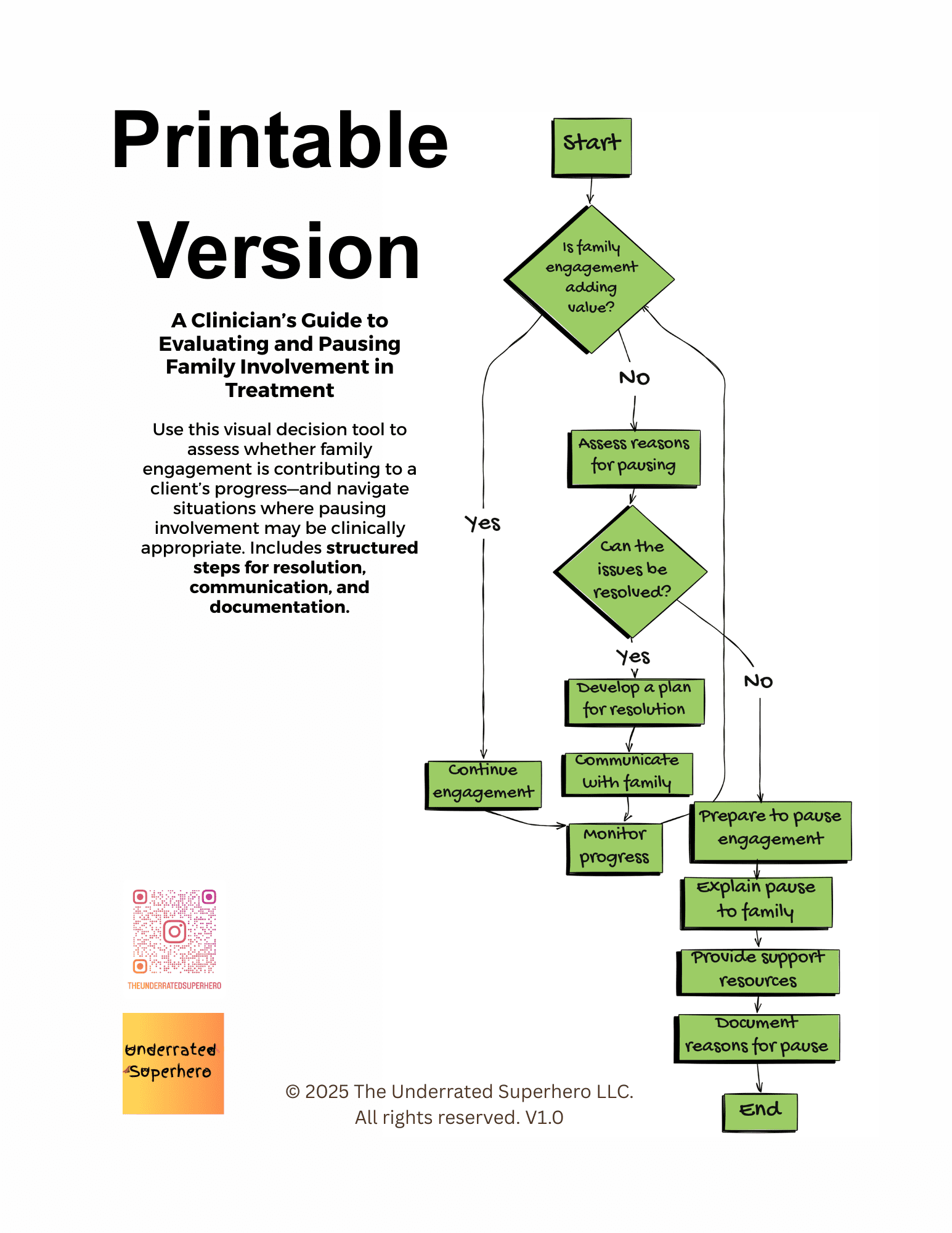

I created “When to Disengage with Family” a flowchart specifically for this. It’s a decision tool for figuring out whether family engagement is actually contributing to progress or whether pausing involvement might be the more appropriate clinical choice. Because sometimes the most helpful thing you can do is recognize when these sessions are doing more harm than good.

📊 Free Clinical Decision Tool: When to Disengage with Family (Click to preview)

When to Disengage with Family: A Clinician’s Decision Guide

Download Free Flowchart →Free account required to access

But honestly? Most of the time I’ve had to pause family sessions, it wasn’t because I thought I was making it worse. It was because everyone—including the family—could see it wasn’t helpful anymore. We all agreed.

I understand there are probably situations where a clinician needs to make that call even when the family disagrees. I’ve just never had to do it, and I’m honestly not sure how I’d handle it if I did.

The Hardest Clinical Balancing Act

What I do know: advocating for your client’s autonomy while honoring parents’ legitimate concerns is one of the hardest clinical balancing acts. And when it falls apart, it usually isn’t because you failed. It’s because the family system is struggling, and you’re the one trying to hold space for everyone’s pain at the same time.

Most of the time when sessions feel like disaster, I don’t think you’re making it worse. You’re just present for the struggle.

But I can’t be totally sure about that.

When You Actually Are Making Clients Worse

The Feedback I Didn’t Want to Hear

Let me tell you about the time I know I messed up.

I was working with a teen and his family. Things started well—I was engaged, energetic, focused on building the relationship and working toward their goals. I thought we were making progress. I really did.

But the parent didn’t agree.

They told my supervisor—not me, my supervisor—that I had “deteriorated.” That over time they’d seen me decline in appearance, mood, energy. That I’d started focusing on things that shouldn’t have been priorities while ignoring their legitimate concerns about their child. That I was focusing on the therapeutic relationship when I should have been addressing more pressing issues.

I was surprised. Honestly, I was defensive at first. We’re making progress, what are they talking about?

But they were right about some things.

The Reality of Burnout

I was working multiple jobs. My chronic illness was flaring badly. Clinician burnout is a well-documented phenomenon that affects not just the therapist, but the quality-of-care clients receive. I was burned out in ways I wasn’t fully acknowledging to myself, let alone to anyone else. And while I don’t think I was providing harmful care—I was still showing up, still trying—I definitely wasn’t at my best. I was being mediocre. Not the clinician I wanted to be. Not operating at the standard I’d set earlier in treatment that they’d come to expect.

Recognizing and managing clinician burnout isn’t just about self-care tips—it’s about building systemic safeguards that catch you before you reach crisis.

The Unrealistic Standard

I remember attending a training once where the speaker said that when a therapist is not at their best, they need to cancel their session. That it’s their responsibility to show up 100% for their client, and anything less is unethical.

That sounds great in a training room. It’s much harder to believe when you’re living it.

What does “not at your best” even mean? A bad night’s sleep? A chronic illness flare? Grief? Burnout from systemic overwork? If I canceled every session when I wasn’t at 100%, I would have had to quit my job entirely. My clients would have had no counselor at all instead of one operating at 70%.

The Choice I Made

I don’t know. Maybe that trainer was right and I was wrong. Maybe showing up imperfectly was more harmful than not showing up. But I also know that the kids I worked with in schools didn’t have a line of qualified counselors waiting to step in if I called out sick. They had me, or they had nobody.

So I showed up. Not at my best, but present.

And then I made it worse.

The family asked for documentation to be completed on a tight deadline. I couldn’t get it faxed in time. Unfortunately, instead of immediately telling them or just sending it directly so they could handle it themselves, I waited. I told myself I’d try again the next day.

I don’t even know what I was thinking. Probably just exhausted and not focused and avoiding the discomfort of admitting I’d failed to follow through.

When I finally sent it and got a message asking why it took so long—you could hear the anger underneath—I knew. I messed up.

The family told my colleague they wouldn’t be coming back to the agency. My supervisor told me directly: “You really messed up.”

She was right.

The Part That Makes This Messier

The Accountability Conversation

When my supervisor told me about the family’s concerns, I was defensive at first. I wanted to explain what I’d been working on, why I’d made the clinical choices I had. But the more I sat with it, the more I realized: regardless of my intentions or my reasoning, the family felt unheard and let down.

My supervisor suggested I could have done more family case management—more regular updates so they felt informed about what was happening in sessions, even when the teen was making progress. She was right. That would have helped.

But I’m still left holding this question: Was I genuinely deteriorating in ways that harmed this family? Was I making my client worse instead of better? Or were they frustrated their kid wasn’t magically fixed, and I wasn’t communicating progress in ways that made sense to them? I don’t know. I really don’t.

Was I Really Making My Client Worse?

But I’m still left holding this question: Was I genuinely deteriorating in ways that harmed this family? Was I making my client worse instead of better? Or were they frustrated their kid wasn’t magically fixed, and my colleague amplified their dissatisfaction into something bigger?

I don’t know. I really don’t.

I know I messed up the letter situation—that’s clear. I failed to communicate and follow through, and it damaged trust in ways I couldn’t repair. That’s on me.

The Nuance That’s Hard to Hold

But the rest of it? I was burned out. I was dealing with chronic illness. I was working in a system that expected me to maintain excellence without any support structure. Research shows annual turnover rates in substance abuse and behavioral health treatment facilities range from 31-50%, with residential and intensive settings experiencing even higher rates. I probably wasn’t at my absolute best. But I was still giving adequate care. I wasn’t being a poor counselor—I was being a human one who was overextended.

There’s a difference between “not at your absolute best” and “causing harm,” and I’m still not entirely sure where I landed on that spectrum.

I went through spirals questioning my entire profession around that time. Maybe I still am, a little.

How to Know If You’re Making Clients Worse

So how do you know when you’re actually making clients worse versus when you’re just present for someone else’s hard journey? When does “not at your best” cross the line into causing harm?

I wish I had a clear answer for this. I don’t.

When It’s NOT About Making Clients Worse

But here’s what I’ve noticed:

- If a client says “this isn’t working” or “this is a waste of time” in the first few sessions—especially if they didn’t want to be there in the first place—it’s almost certainly about them getting used to the discomfort of therapy. Not about your competence. That’s their journey, not your failure.

- If you’re working without adequate resources, in hostile environments, with impossibly high caseloads and no support—the system is failing both you and your clients. That’s not the same as you failing them. Though I’ll admit, in the moment, it sure feels like the same thing.

- If family sessions involve ruptures, if clients push back, if moments get uncomfortable—that might just be therapeutic work happening. Discomfort doesn’t always mean damage. Sometimes it means progress. I have to remind myself of this constantly.

- If you’re hearing secondhand that someone’s unhappy but they haven’t told you directly—consider whether workplace dynamics or systemic issues are in play before you spiral. Not saying the feedback isn’t valid, just that context matters.

Red Flags You Might Be Making Things Worse

- If you’re consistently burned out or impaired—physically exhausted, mentally checked out, dealing with untreated chronic illness or mental health issues—you might not be providing the level of care your clients deserve. The ACA Code of Ethics addresses clinician impairment and the responsibility to monitor your own wellness and effectiveness. Need a quick reference? Our Ethics Codes Reference Sheet consolidates key principles across ACA, NASW, and addiction counseling codes for rapid clinical decision-making, requires free account.

📋 Quick Reference: Ethics Codes Reference Sheet (Click to preview)

Quick Reference Guide: Ethical Codes & Standards for Addiction Professionals

A concise overview of key ethical codes and standards that guide professional conduct, ensuring compliance, accountability, and ethical integrity in practice.

NAADAC Code of Ethics

- Professional conduct for addiction counselors

- Client welfare, confidentiality, and cultural sensitivity

- Professional boundaries and ethical decision-making

- Dual relationships and conflict of interest

- Mandated reporting and legal obligations

ACA, APA, NASW Ethical Standards

- ACA: Professional integrity, informed consent, ethical assessments

- APA: Ethical principles in research, therapy, dual relationships

- NASW: Social justice, advocacy, ethical responsibilities

State Licensing Boards & Legal Mandates

- Legal and ethical standards enforcement

- HIPAA and 42 CFR Part 2 compliance

- State-mandated reporting laws

- Telehealth regulations and cross-state licensure

Includes reflection questions: How do these guidelines impact your daily decision-making? Are you fully compliant with ethical requirements? What areas need further development?

✓ Free download — Requires free account login

- If multiple clients aren’t returning after initial sessions—one client not coming back could be anything. A pattern might mean something about your approach, your intake process, your ability to establish safety quickly enough. Or it might not. I honestly don’t know how to tell sometimes.

- If you make a mistake and your instinct is to avoid it—like I did with that letter deadline—that’s a red flag. If you’re minimizing, deflecting, waiting to address it “later” because it’s uncomfortable now, that’s when you might be making things worse.

- If supervision or colleagues are raising consistent concerns—not every piece of feedback means you’re failing. But if multiple people in different contexts are noticing the same issues, it’s probably worth taking seriously. Even if one of those people has their own agenda.

I’m still figuring out how to balance “I’m only human” with “but I still need to be accountable.” It’s harder than I expected.

What to Do When You Actually Mess Up

Apologize directly and specifically.

Not “I’m sorry you feel that way” or defensive explanations about why you couldn’t do the thing. Just: “I didn’t follow through on the letter deadline I committed to. That wasn’t acceptable, and I understand it damaged your trust in me. I’m sorry.”

I’m not great at this. I get defensive. But I’m trying to get better.

Admit when you’re wrong without deciding you’re a terrible clinician who should quit. The art project disaster taught me I’m human and I make mistakes. The letter situation taught me I need better systems for tracking commitments when I’m overextended. Neither of those things means I’m unfit for the work.

Though some days I wonder.

Get Real Supervision

Get real supervision. Not only the kind where you present cases professionally and discuss interventions. The kind where you can say “I got called out for deteriorating and I don’t know if they’re right and I can’t stop crying” and your supervisor doesn’t try to fix it or give you a pep talk. They just sit with you in it. Need more than that? Enroll in therapy yourself.

I didn’t always have that. I wish I had.

Build in safeguards if you’re overextended. Shared calendars. Accountability partners. Regular check-ins with colleagues who will tell you honestly when you seem off. My High-caseload documentation systems—including spreadsheet templates and workflow guides—can prevent the kind of letter deadline failure that damages trust by helping you stay organized even when you’re overworked. I wasn’t tracking that type of work at that time and have since learned to track all deadlines and commitments with systems. These systems are available on my site free of charge, just requiring a free account login.

📊 Featured Resource: The High-Caseload Success Guide (Click to preview)

Featured Resource

Now Available in Your Member Library

The High-Caseload Success Guide

How I Managed 80+ Clients with Top Retention Rates

- ▶ Digital Mastery — iPad workflows & EHR optimization

- ▶ Strategic Information Management — 5-spreadsheet system

- ▶ Template Efficiency — 60% documentation time reduction

- ▶ Bulletproof Workflows — Zero compliance gaps

- ▶ Performance Metrics — Data-driven improvements

- ▶ Client Engagement — Proven retention strategies

✓ Included with your free membership — No additional signup required

Know when to refer out. Sometimes the most helpful thing you can do is recognize you’re not the right fit—whether because of your current capacity, your theoretical approach, your personal limitations, whatever is a critical clinical skill that protects both the client and the therapeutic relationship. Recognizing when continuing to work with someone means you might be making them worse instead of better? That’s not failure. That’s ethical practice.

I think. I hope.

What I’d Tell You Now

It’s Not Your Fault the System Is Broken

If you’re sitting in your car after forgetting the art supplies, after a family session fell apart, after getting feedback that you’re not meeting expectations—

It’s absolutely not your fault that you don’t have adequate materials. That should not be your responsibility to purchase. Those resources should be provided by the school, by your agency, by someone other than you. The fact that they’re not is a systemic failure, not a personal one.

You’re human. You will make mistakes. Some of those mistakes will hurt people, and you’ll need to own that and do better. That’s uncomfortable and it sucks and there’s no way around it.

But most of the time when you feel like you’re making it worse? I think you’re probably not. I think you’re just holding space for how hard this work actually is. For your clients and for yourself.

The Fear Means You Care

The fear that you might be making clients worse—that you might be someone’s horror story—that fear means you care enough to question yourself. That’s not the hallmark of a bad clinician. That’s actually probably a sign you’re taking your impact seriously enough to worry about it.

Sometimes you need to hear that you’re doing okay even when it doesn’t feel like it. Even when the group is fragmented and the family is disengaging and you forgot the damn paint. Even when you’re operating at 70% capacity instead of 100% because chronic illness and systemic overwork mean that’s all you have right now.

Adequate care during burnout is still care. Mediocre performance while chronically ill is still showing up. And showing up imperfectly is almost always better than the alternative of no one being there at all.

But Don’t Let It Become an Excuse

Just don’t let “I’m only human” become an excuse to avoid accountability when you genuinely mess up.

Learn to tell the difference between “I’m struggling within an impossible system” and “I’m the one creating the problem.”

I’m still working on that part.

Want more support for navigating difficult clinical situations? Explore our free resources for new clinicians including our worksheet, tools, and more. Must create a free account to access resources.

Additional Support Resources

Free Clinical Tools:

- When to Disengage with Family: Decision Guide – Flowchart for evaluating family therapy effectiveness

- Ethics Codes Reference Sheet – Quick comparison of ACA, NASW, and addiction counseling ethical standards

- High-Caseload Success Guide – Complete documentation system with spreadsheet templates and workflow guides

Professional Development:

- First 90 Days Survival Kit – Scripts, self-assessment tools, and guidance for new clinicians

- New Clinician Resource Hub – Comprehensive support for early-career counselors

Next Week: We’re tackling another brutal truth that keeps clinicians up at night. See you then!

Stay Strong | The Underrated Superhero

© 2025 The Underrated Superhero LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Resources Referenced in This Post

- SAMHSA: Understanding Compassion Fatigue – Guide on recognizing and addressing compassion fatigue in behavioral health professionals

https://library.samhsa.gov/product/understanding-compassion-fatigue/sma14-4869 - American Psychological Association: Psychologist Burnout – Research on clinician burnout and its impact on client care

https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/01/special-burnout-stress - American Psychological Association: Rupture and Repair in Psychotherapy – Clinical approaches to understanding and resolving therapeutic ruptures

https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/rupture-repair-psychotherapy - ACA Code of Ethics – Professional standards on clinician impairment and wellness monitoring

https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Previous posts in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series:

Week 1: I Hate Group Therapy: How I Went from Dreading sessions to Loving Them

Week 2: I Can’t Do This: When Imposter Syndrome for Therapists Hits Hardest

Week 3: My Client Hates Me: When Resistance Feels Personal