Blog #3 in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series (“My Client Hates Me“)

“This is not about me” vs “My client hates me”

I still have to remind myself of this. Even after years of doing this work, I feel that familiar pang when a client chooses to work with another clinician. I know all about good fit. Transference makes sense to me theoretically. I can explain intellectually why someone might connect better with a different therapist. But knowing it and feeling it are two different things.

“My client hates me.”

If you’ve thought this – even once – you’re in good company. If you’ve ever felt like a client hates you or experienced the sharp sting of parent hostility in therapy, you’re not broken. You’re human. Just like feeling overwhelmed by group therapy or questioning whether you can handle the work, feeling rejected by clients is a common experience that nobody warned you about. And you’re probably not wrong about sensing hostility. The question isn’t whether they’re upset. The question is: what’s really going on, and how do you tell the difference between projection and legitimate feedback?

When Client Aggression Feels Like “My Client Hates me”

Early in my career, I worked in residential treatment settings. I was bitten, hit, and attacked. There were attempted strangulations. Client aggression happened so regularly that I cried, processed with colleagues and reminded myself daily that I wasn’t awful or weak for struggling with it.

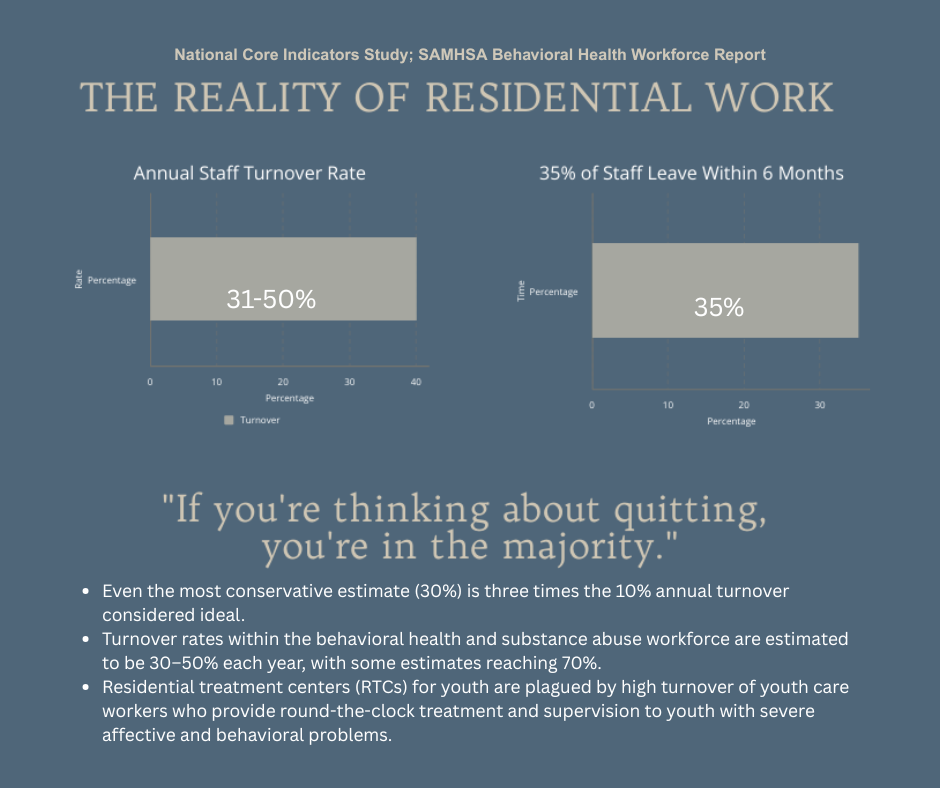

The average length someone stays in those jobs? Four months. Research shows annual turnover rates in substance abuse and behavioral health treatment facilities range from 31-50%, with residential and intensive settings experiencing even higher rates. According to a National Core Indicators study, an estimated 35% of new hires in behavioral health turnover in six months or less.

I stayed almost a year, thinking every single day that I should quit.

Why Violence Feels Personal (Even When It’s Not)

Here’s what made it so hard: when a client physically attacks you, it’s almost impossible not to think “they must hate me.” How could someone you’re trying to help mistreat you this way? How could the therapeutic relationship mean so little that they’d hurt you?

With younger children, I can see the truth more easily – they have minimal ability to regulate emotions. They’re not attacking you; they’re attacking whoever’s there when they’re dysregulated. You can see it’s not personal, even when it hurts.

But with older teens and adults? They’re better at making it feel like it’s actually about you, the provider. They know what to say, how to make it cut deeper. The hostility feels targeted and intentional in ways that are harder to separate from your sense of self.

The Self-Doubt That Follows Repeated Attacks

After repeated physical incidents, you start to question everything. Maybe I’m not cut out for this work. Maybe there’s something about me that triggers aggression. Could I be the problem?

Here’s what helped me: understanding that aside from a few clients with psychotic tendencies, most didn’t actually hate me. Many of them liked me. But I was there when their emotions overwhelmed their capacity to cope, and their dysregulation found the nearest target.

That doesn’t make it okay. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t protect yourself or set firm boundaries. But it does mean the violence isn’t about you, even when it feels intensely personal.

Processing “My Client Hates Me” Through Supervision

If you work in settings where client aggression is common, you need regular supervision. Not the kind where you present a case professionally and discuss interventions. The kind where you say “I got punched in the face today and I can’t stop crying and I don’t know if I can go back tomorrow” and your supervisor doesn’t try to fix it, just sits with you in it.

You need colleagues who understand clinical supervision for processing difficult therapeutic relationships and won’t minimize your experience. Who don’t say “it comes with the territory” like that makes it hurt less. Who let you rage about how unfair it is without reminding you about trauma responses and dysregulation – you know all that, it doesn’t make the bruises disappear.

You need permission to fall apart. To question whether you should stay. To admit that some days you hate this job and everyone in it. That doesn’t make you weak or unsuited for the work. It makes you someone who hasn’t been completely desensitized yet, which is probably a good thing even though it doesn’t feel like it.

And look – you need actual safety protocols, not the kind in the employee handbook that nobody follows because there aren’t enough staff. But that’s a different essay about systemic failures in residential care.

Physical aggression is the most extreme form of what feels like client hatred. But the emotional dynamics that make it hurt—the sense of rejection, the questioning of your competence, the feeling that you’ve somehow failed—show up in subtler forms of resistance too. And sometimes those subtler forms cut even deeper because they’re harder to name and process.

From ‘My Client Hates Me’ to Understanding Countertransference

What’s interesting is how my response to hostility has shifted over my career.

Early on, client aggression devastated me. I took it deeply personally even when I could intellectually explain it wasn’t about me. Every attack felt like proof I was failing.

Now? As a parent myself, I find that parent hostility hits me harder than client aggression ever did. When a mother yells at me or questions my competence, I empathize with her fear and desperation in ways I couldn’t before having kids of my own. I want to help her partly because I want to help myself – I see my own potential struggles reflected in her panic.

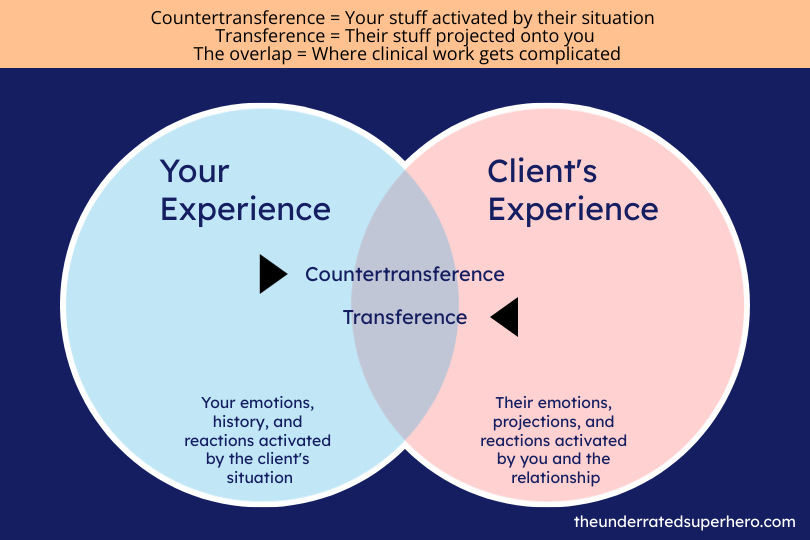

That’s countertransference. Training programs rarely teach therapist countertransference – especially with parents – is rarely taught in training programs, but research shows it’s critical for effective therapeutic work. We all know what it is theoretically. The places where our own stuff gets activated by client situations. Everyone experiences it. That’s not the interesting part.

How Countertransference Shifts as You Change

The interesting part is how it shifts. What guts you changes as you change.

At 25, I could hear stories of parental neglect and feel sad for the kid but maintain distance. Now? Now that I’m a parent myself, those stories hit different. I catch myself thinking “how could they…” and have to pull back, remind myself I don’t know the full story, remember my job isn’t to judge parents but to help the kid in front of me.

And it goes the other way too. Early in my career, when parents questioned my competence, I spiraled. Took it so personally. Questioned everything about myself. Now? Most of the time I can see it for what it is – their fear, their exhaustion, their desperate need for someone to fix an unfixable situation.

Most of the time. Not always.

What you’ll be able to handle at 25 versus 35 versus 45 – it changes. Not in a linear “you get better at this” way. More like… different things land differently depending on what you’re living through outside this office.

When Parents Project Their Terror Onto You

If you work with adolescents or families, you know this reality: sometimes the parents are harder to work with than the clients themselves.

I’ve received messages from parents demanding I terminate services immediately, accusing me of making things worse, insisting I wasn’t addressing the “real issues.” I’ve heard through clients that their parents think I’m ineffective or incompetent. I’ve sat in sessions where parents interpreted every intervention as a personal attack.

My first reaction is always the same: What did I do wrong?

The familiar ‘my client hates me’ spiral begins.

Then comes the mental review of every interaction, every decision, every word choice. Even experienced clinicians do this. And honestly? We should. These concerns could be legitimate and need to be taken seriously.

But here’s what I’ve learned: most of the time, parent hostility has very little to do with you.

They’re projecting their own fears. Their child is decompensating, using substances, or struggling in ways they can’t control. You’re the most visible target for that terror.

Parents are exhausted. By the time families get to therapy, they’ve been fighting this battle for months or years. They want immediate results because they’re desperate.

They want you to be the parent. They expect you to punish their child, set their boundaries for them, teach life skills, and somehow make their teenager respect them – all in 50-minute sessions.

They’re dealing with their own stuff. Unresolved trauma, relationship conflicts, their own substance use, mental health struggles – all of it gets activated when their child is in crisis.

The Gap Nobody Prepares You For: When Families Make You Feel Inadequate

Here’s what they teach you in training: stay in your lane. If a family needs systemic family therapy and that’s not your specialty, refer them to a specialist.

Here’s what actually happens in the real world: maybe 5% of the time, that referral works smoothly. Research on primary care referrals shows that only 35% of referrals result in completed specialist appointments. The other 95% of the time? You’re trying to do what you can for your client and their family despite your limitations.

Why the disconnect? Because family therapy waitlists are months long. There are few providers. It’s expensive. And families just want to meet with someone – and if they feel comfortable with you, you’re their person.

Clinicians understand the distinction between individual therapy with family involvement versus actual systemic family therapy. But clients and their families? They’re desperate for help and confused about why you’re sending them somewhere else when they finally found someone they trust.

So you end up doing your best with the tools you have, knowing you’re not a trained family therapist, trying to support your client while including their family in ways that help rather than harm.

And sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t. And many times parents blame you for not being something you never claimed to be.

When Parents Project Their Marriage Onto You

I once worked with a family where the father seemed hostile from day one. Every suggestion felt like a confrontation. Every boundary I set was questioned. Sessions felt tense in ways that didn’t match what was actually happening.

It took me longer than it should have to realize: he wasn’t reacting to me. He was reacting to his own unresolved conflicts that I was somehow triggering – maybe my age, my gender, my ethnicity, or simply that I represented someone else in his life he was struggling with.

That’s transference. And while we’re trained to recognize it in clients, nobody really prepares you for parent transference.

The hard part? Even when you know intellectually that someone’s reaction isn’t about you, it still feels personal. You still question yourself. You still wonder if you’re missing something.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Ruminating on ‘My Client Hates Me’

When a parent sends a hostile message or a client physically attacks you or requests a different therapist, you’re going to ruminate. That’s normal. That’s healthy, actually.

Here’s the key: there’s a difference between productive reflection and destructive rumination.

Productive reflection asks:

- What were the facts of what happened?

- Is there a pattern here I need to address?

- What would I tell a supervisee in this situation?

- Is there legitimate feedback I need to hear?

Destructive rumination sounds like:

- I’m a terrible therapist

- Everyone hates me

- I should just quit

- I can never do anything right

The first helps you grow. The second keeps you stuck.

Process productive reflection with your supervisor—especially when the ‘my client hates me’ thoughts feel overwhelming. Don’t do this alone. When I’ve received particularly difficult feedback, experienced physical aggression, or navigated parent hostility, I’ve always consulted with clinical supervision to process difficult cases before responding. That consultation helps me stay grounded and professional instead of reactive and defensive.

When Client Reports Become Weapons

- “My mom says you’re not helping.”

- “My dad thinks you’re an idiot.”

- “They want me to see someone else.”

Clients report what their parents say about you, often triggering that ‘my client hates me’ feeling all over again. Sometimes it’s accurate. Often, it’s filtered through the client’s own feelings, distorted by their confusion, or weaponized to avoid accountability.

Here’s what I typically tell clients when this comes up: “That happens sometimes. Your parents don’t know what we talk about because of confidentiality, so they make assumptions based on what you tell them. I’m acting in your best interest, which sometimes means your parents feel unsupported or excluded. That’s hard for everyone, but it’s part of protecting your privacy.”

Most clients understand this explanation. It helps them make sense of why their parents might be frustrated without feeling caught in the middle.

But I also stay open to the possibility that parents have legitimate concerns. Maybe I’m missing something. Maybe there’s a cultural blind spot I haven’t addressed. Maybe my approach genuinely isn’t working for this family.

The key is staying curious instead of defensive.

When “My Client Hates Me” Is Actually About You

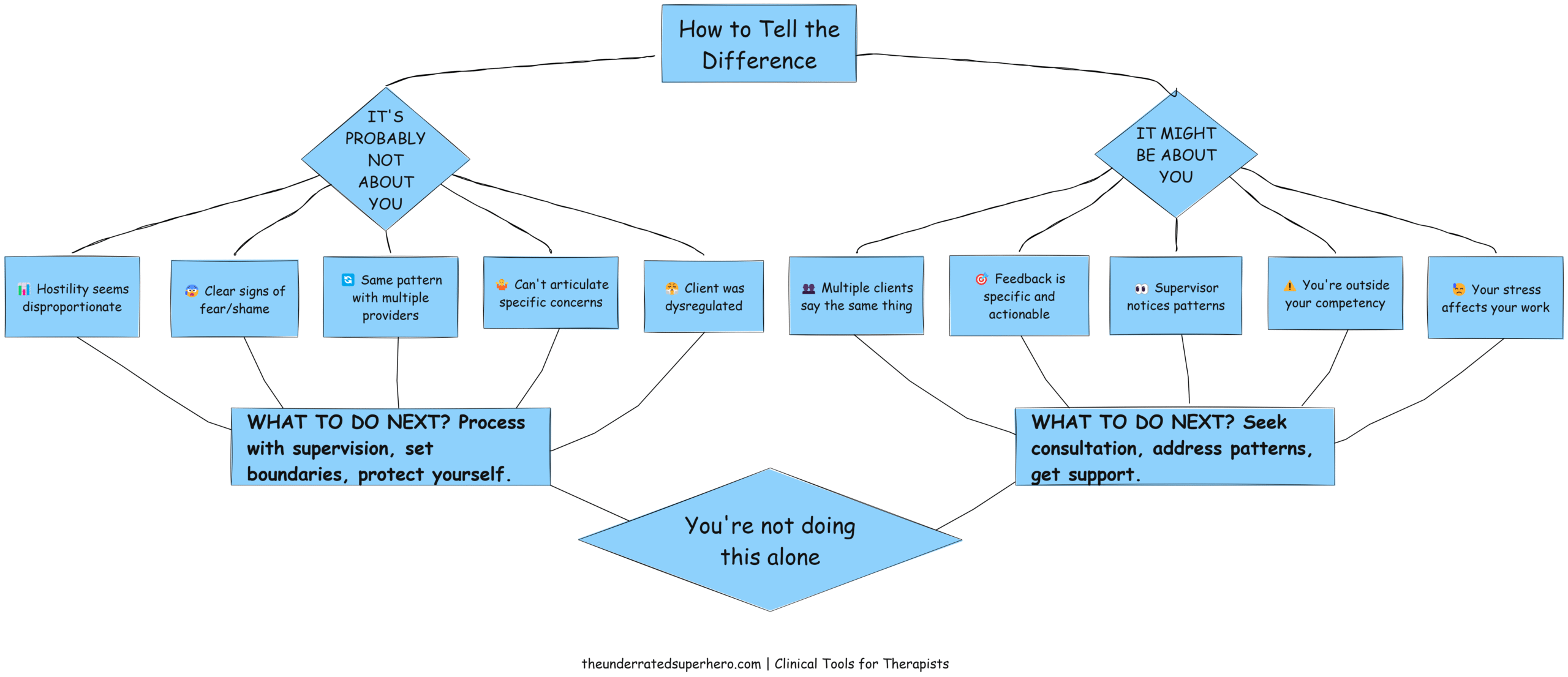

Sometimes the feedback is valid. At times you are outside your competency. It’s possible a client would be better served by someone else.

Research shows that between 20-57% of therapy clients don’t return after their initial session, with dissatisfaction with the therapist cited as the number one reason for premature termination.

Signs You Can’t Ignore

When you hear the same criticism from multiple families – not just “you’re not helping” (everyone gets that eventually), but specific things. “You talk too much in session.” “You never address what I bring up.” “You seem distracted.” That’s pattern data you can’t ignore.

When your supervisor notices something you’ve been defensive about. When they bring it up gently and your immediate reaction is to explain why they’re wrong. That reaction? That’s usually the tell that they’re onto something.

When you’re working outside your training because you feel like you should be able to figure it out. I did this with my first family with active domestic violence – kept thinking “I’m smart, I can handle this” instead of “I have no idea what I’m doing and someone could get hurt.” Pride disguised as dedication is still pride.

The Cultural Competency Question

When there’s a cultural or identity mismatch you haven’t acknowledged. Early in my career, I worked with a lot of immigrant families as a white American clinician who’d never left the country. I didn’t know what I didn’t know. And yes, in those cases, my feeling that ‘my client hates me’ might have been picking up on a legitimate mismatch.

When Burnout Becomes Visible

When you’re so burned out that you’re irritable in sessions. When you’re relieved when clients cancel. When you catch yourself being subtly dismissive because you just cannot hear another crisis today. That’s about you, not them. And it means you need help before you cause harm.

Early in my career, looking young was both an advantage and a disadvantage. With adolescents, it helped – they trusted me faster, felt I understood them better. With some parents, it created credibility issues I had to navigate carefully.

Good fit matters. Life experience matters. Cultural matching matters. And acknowledging when you’re not the right fit isn’t failure – it’s ethical practice.

When You Think “My Client Hates Me” – What’s Really Happening

“My client hates me” is one of those thoughts that feels shameful to admit, even to supervisors. But it’s also one of the most common thoughts in clinical practice.

Get out of your own head. When you notice yourself spiraling into “they hate me” thoughts, pause and remind yourself: This is not about me. I don’t know what’s really going on. I need to understand. Then focus on validation before problem-solving.

Talk to your supervisor. Don’t process client aggression or parent hostility alone. You need outside perspective to distinguish between projection and legitimate feedback. You need help figuring out how to respond professionally without getting triggered or defensive.

Communicate regularly with parents. Does this prevent them from hating you? Not always. But it does reduce confusion about what’s actually happening in treatment. It gives clients context for why their parents might be frustrated. And it provides documentation when conflicts escalate.

Be upfront about your scope. If you’re not a trained family therapist but offering family sessions, say so. If you’re new and still building certain skills, that’s okay to acknowledge. Families often respect honesty more than false confidence.

Know when it’s not the right time. Sometimes the client, family, or situation just isn’t ready for the work you can offer. That’s reality, not failure.

The Pattern That Repeats: When Client Hostility Becomes a Cycle

Here’s a scenario that happens more often than anyone talks about: A parent sends you an angry message demanding you terminate services. They’re furious about something – maybe their child got worse before getting better, maybe you recommended additional services they see as criticism, maybe they just don’t trust the process. They insist treatment ends immediately.

You process it with your supervisor. You reflect on what happened. You wonder what you could have done differently.

Then the client – or sometimes the other parent – reaches out to schedule the next session. The client wants to continue. Treatment isn’t actually ending.

Here’s what nobody tells you: in that moment, you don’t feel relief or vindication. You feel a kind of resigned dread – what I think of as “the head slump.”

Why? Because you know this pattern will likely repeat. The parent’s fear, their need for control, their unresolved trauma – none of that changed just because their child wants to continue therapy. You’re about to walk back into the same dynamic that created the blow-up in the first place.

So you keep showing up. You keep trying to support the client while managing the parent’s anxiety. You keep walking that impossible line between honoring confidentiality and keeping the parent engaged enough that they don’t sabotage treatment.

And sometimes it works. The client makes progress despite family chaos. The parent eventually trusts the process. Treatment succeeds in ways nobody expected.

And sometimes it doesn’t. The family finds another therapist. The pattern repeats there too. Or the client gets stuck between your recommendations and their parent’s demands and progress stalls.

Either way, you did your best with an impossible situation. That has to be enough.

The Uncomfortable Middle Ground Between “My Client Hates Me” and “It’s Not Me”

Most of the time when clients physically attack you or parents seem to hate you, it’s not about you. But you should still reflect to make sure.

And even when you know intellectually that it’s not about you – when you can clearly see the dysregulation, the transference, the projection, the fear, the exhaustion – it can still feel intensely personal.

That feeling doesn’t make you weak or insecure. It makes you human.

The difference between new clinicians and experienced ones isn’t that veterans don’t feel that sting anymore. It’s that they’ve learned to feel it, reflect on it, process it with supervision, and then let it go.

They’ve learned to ask: “What might this behavior be communicating that has nothing to do with me?”

They’ve learned to distinguish between their own insecurity and legitimate feedback that requires change.

They’ve learned that caring deeply about whether you’re helping people makes you vulnerable to feeling rejected – and that vulnerability is actually a strength, not a weakness.

They’ve learned that what feels most personal shifts over time as you grow and change.

Your Turn

The next time you think “my client hates me”:

Pause. Take a breath before reacting or responding.

Get curious. What might be driving this reaction that has nothing to do with your competence?

Reflect honestly. Is there a pattern here? Is there valid feedback I’m avoiding?

Process with others. Talk to your supervisor, consultation group, or trusted colleague. Don’t stay stuck in your own head.

Respond professionally. Even when you feel attacked, respond to the content of concerns rather than the emotion behind them.

And remember: the fact that you care enough to wonder if it’s about you probably means you’re doing better than you think.

Want more support for navigating difficult clinical situations? Explore our free resources for new clinicians including our worksheet, tools, and more. Must create a free account to access resources.

Ready to build the confidence and reflective practice habits that separate overwhelmed therapists from thriving ones? Our 90-Day New Clinician Confidence Planner helps you track patterns across difficult cases, process complex therapeutic relationships, and develop the clinical judgment that only comes from structured reflection. It’s designed specifically for clinicians navigating their first years in the field—when everything feels personal and nothing feels certain.

Want comprehensive training, community support, and ongoing clinical consultation? Join our membership community to get access to interactive training modules, frameworks, and a network of clinicians who understand exactly what you’re going through.

Next Week: We’re tackling another brutal truth that keeps clinicians up at night. See you then!

Stay Strong | The Underrated Superhero

Resources Referenced in This Post

- SAMHSA Behavioral Health Workforce Report – National data on substance abuse treatment facility staffing and turnover Link: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-survey-substance-abuse-treatment-services-n-ssats-2020-data-substance-abuse

- National Core Indicators Study – Research on behavioral health workforce turnover rates Link: https://www.onshift.com/resources/blog/turning-around-employee-turnover-in-behavioral-health

- Closing the Referral Loop Study – Analysis of referral completion rates in healthcare Link: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/fpm/issues/2015/0300/p12.html

- Psychotherapy.net: Understanding Therapy Dropouts – Research on client premature termination Link: https://www.psychotherapy.net/article/therapy-dropouts

- Body-Centered Countertransference Research – Study on countertransference in therapeutic relationships Link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3330620/

Previous posts in the New Clinician Survival Kit Series:

Week 1: I Hate Group Therapy: How I Went from Dreading sessions to Loving Them

Week 2: I Can’t Do This: When Imposter Syndrome for Therapists Hits Hardest