Blog #1 in the Justice-Involved Treatment Mastery Series: Harm Reduction with Mandated Clients

What Harm Reduction with Mandated Clients Looks Like

Fifteen years into my career conducting harm reduction with mandated clients, I thought I understood the challenges. Then a new court official decided my clinical judgment wasn’t good enough.

I had submitted a progress report on a teen who was finally coming to treatment regularly, opening up in sessions, and genuinely participating for the first time. Yes, he was still testing positive for THC, but he was engaging in ways I hadn’t seen before. The court official dismissed this progress entirely. They wanted dramatic lifestyle changes—complete abstinence, perfect grades, stellar employment or a higher level of care. The small but meaningful steps this kid was taking weren’t enough. They wanted to remove him from the program because he “wasn’t making progress fast enough.” This was a perfect example of why harm reduction with mandated clients creates such tension with traditional court expectations.

This wasn’t just about one individual. Rather, it highlighted something I see constantly: the assumption that abstinence equals progress and any substance use equals failure. Even after fifteen years in this field, I was still encountering people who couldn’t see past black-and-white thinking about recovery. This experience crystallized a fundamental insight that guides everything when I do harm reduction with mandated clients.

When Good Progress Isn’t “Good Enough”

In my last blog, we explored why traditional compliance-focused approaches often fail justice-involved clients. We talked about moving beyond punishment toward care. We discussed recognizing trauma responses and why “mandated” doesn’t have to mean “meaningless.” But here’s where many counselors get stuck: “What do I actually do when the court demands abstinence and my client isn’t ready for that goal?”

This is where harm reduction with mandated clients becomes essential—not as a way to circumvent court requirements, but as a framework that works within those requirements while building genuine change. Court compliance and therapeutic progress aren’t the same thing, but they don’t have to be opposing forces either. For readers unfamiliar with core harm reduction principles, this approach focuses on reducing risks rather than eliminating use entirely.

The False Choice Between Compliance and Evidence-Based Practice

Traditional approaches to mandated treatment operate on a simple premise: follow the rules, complete the program, avoid consequences. This creates what I call “performance recovery” – clients learn to say the right things, show up on time, and pass drug tests while their underlying relationship with substances remains unchanged.

Early in my career, I didn’t even know I was fundamentally drawn to harm reduction principles. I would sometimes push the abstinence agenda because that’s what most community mental health places do. But I found myself feeling frustrated with everyone involved—participants, legal systems, colleagues. Even though there might be some improvement, it certainly wasn’t happening for the majority of people I worked with.

It was a gradual shift, not some lightning bolt moment where I attended one training on harm reduction and was suddenly changed. Looking back, I was doing motivational interviewing before I knew it was called motivational interviewing. That’s because it’s not really a technique if you truly believe that the client is the expert and you’re there to support their journey.

The result of traditional modalities? High dropout rates, low engagement, and participants who relapse the moment supervision ends. However, you don’t have to choose between satisfying legal mandates and providing effective care. Harm reduction with mandated clients works—it simply requires a different application.

Forget what you think you know about harm reduction being “soft” on accountability. When applied thoughtfully with justice-involved populations, harm reduction becomes a powerful tool for both compliance AND genuine change. Years of system involvement teach people that authority figures are threats, not helpers. This aligns with established trauma-informed care principles, see SAMHSA’s work on trauma-informed care.

Principle 2: Expand Your Definition of “Harm”

The first principle sounds counterintuitive but it’s crucial: meet clients where they are, even when they don’t want to be there. Instead of starting with “You’re here because you have a problem with drugs,” try “You’re here because the court wants you here. Let’s figure out how to make this work for you while you’re meeting that requirement.” This isn’t minimizing the substance use or enabling denial. It’s acknowledging the client’s actual motivation and working from there.

Here’s what I’ve learned from years of experience: when I don’t start by demanding clients stop everything they’re doing, I actually get into real therapeutic work much faster. There’s no need to break through that unnecessary wall of defensiveness and mistrust that comes from treating someone like they have no agency or control over their own life. Instead of spending weeks or months trying to convince them they have a “problem,” we can dive straight into what they actually want to change and how their current patterns help or hurt those goals. When you stop fighting about whether they “really” need treatment, you can start having productive conversations about what they actually want to change.

But here’s something equally important: meeting clients where they are also means meeting the courts where they are. I’ve learned to work hard at collaborating with the legal system to ensure they could see progress, even small steps, so they would feel that the approach was working. If I didn’t do this, they would certainly doubt my qualifications and the integrity of the program. This collaboration isn’t about compromising your clinical judgment—it’s about translating genuine progress into language and metrics that the legal system can understand and value.

Principle 2: Expand Your Definition of “Harm”

The second shift involves expanding what we mean by “harm.” Most harm reduction focuses on health and safety risks like overdose prevention or safer use practices. With mandated participants, we need to include harm to their legal situation, relationships, employment, and freedom. I find myself asking questions like “What would need to happen for you to end up back in the legal system?” or “How does your current use pattern affect your ability to meet probation requirements?” These conversations often reveal risks people haven’t fully considered, and they position you as someone helping them protect what matters to them.

Principle 3: Create Choice Within Structure

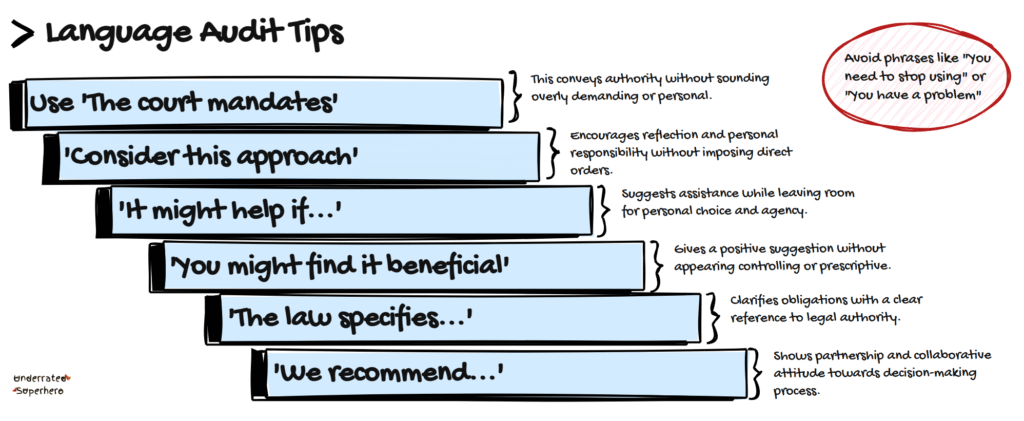

Building autonomy within structure presents the biggest challenge. Court mandates create external requirements, but lasting change requires internal motivation. With harm reduction for mandated clients, you’re creating space for choice and self-direction within the required framework. Instead of saying “The court says you need to attend AA meetings,” try “You need to complete 12 mutual support meetings. Let’s explore what options might actually be helpful for your situation.” This small language shift transforms a mandate into a collaborative planning process.

Practical Strategies for Harm Reduction with Mandated Clients

Progress metrics need reframing too. Instead of measuring days sober, track metrics that matter to both the court and the client. Days without legal complications, successful completion of probation check-ins, maintained employment or housing, reduced conflict with family or partners. These indicators often predict long-term success better than abstinence measures, and they align with what courts actually care about most.

The Court Success Plan in Action

Let me show you what this looks like in practice. Here’s a framework I’ve developed that satisfies both court requirements and therapeutic goals. I call it the “Court Success Plan.” You work collaboratively with clients to identify specific behaviors that could jeopardize their legal situation. This isn’t traditional relapse prevention focused on triggers and cravings. Instead, it’s practical risk management that serves both court compliance and harm reduction goals. When you document this in treatment notes, you might write something like “Client identified high-risk situations that could impact court compliance and developed specific strategies to manage these situations.” The court sees evidence of progress toward their goals, while the client feels ownership over their choices.

Finding the Minimum Effective Dose

There’s also tremendous value in what I think of as the “minimum effective dose” approach. Help clients identify the smallest changes that will produce the biggest impact on their legal situation. This respects their autonomy while moving toward meaningful change. Sometimes that means not using before court appearances, avoiding certain people or places during probation, or having a solid plan for high-risk situations. These might seem like small steps, but they often create momentum for bigger changes down the road.

Addressing the Elephant in the Room: “But What About Abstinence Requirements?”

Many courts require abstinence as a condition of probation, which doesn’t eliminate harm reduction with mandated clients but changes how you apply it. Harm reduction with mandated clients under abstinence requirements means helping clients understand the difference between a lapse and a full relapse, teaching strategies to minimize consequences if use occurs, creating plans for immediate stabilization after any use, and connecting clients with resources that support long-term abstinence. The goal isn’t helping clients circumvent court requirements but helping them succeed within those requirements while building genuine motivation for change.

Navigating Professional Pushback

In the beginning, I had to build trust with the legal team, and often that meant riding that fine line between harm reduction and abstinence approaches. I think new clinicians need to feel comfortable with feeling uncomfortable—like when others, whether legal professionals or even other clinicians, don’t always approve of the work you’re doing. That just comes with the job.

I remember running groups in schools where I was referred all the kids who got in trouble—which wasn’t a problem, though it showed the school was being reactive rather than preventive. My groups would be interactive and relatively fun, even while discussing serious things. The dean would get so annoyed, saying it was all “fun and games for bad kids.” Normally I’m used to this kind of pushback from others, but his animosity caught me off guard. Here I was, actually engaging kids who usually shut down completely, and he saw it as rewarding bad behavior.

This is why supervision and peer consultation are paramount, because imposter syndrome is real when you’re pioneering a different approach. But as my opening story shows, even with fifteen years of experience, there will still be people who disagree with your clinical judgment. What matters most is advocating for your client based on evidence and professional expertise, not on what’s easiest or most popular with the system.

Understanding “Gaming the System”

I’ve found that when counselors worry about “enabling” participants by not being strict enough, they’re usually operating from fear rather than clinical judgment. Yes, some people might try to game the system—but even then, we should ask why.

Substance use and mental health issues typically stem from trauma, and we’re dealing with very traumatized individuals. If someone is manipulating or trying to work around requirements, that behavior itself is often a trauma response developed as a survival mechanism.

The most effective modalities acknowledge that setbacks happen while maintaining clear expectations about moving forward. This means having honest conversations about what happens if someone uses, how to handle it safely, and how to get back on track quickly. These conversations often prevent small slips from becoming major relapses that land people back in legal trouble.

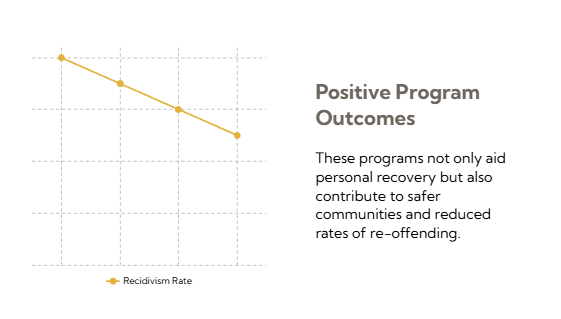

Harm Reduction with Mandated Clients: Why This Matters More Than Ever

The evidence supports this approach consistently across different programs and populations. Justice-involved individuals represent a significant portion of addiction treatment admissions, yet most counselors receive little training on how to work effectively with mandated populations. The result is frustrated counselors, disengaged participants, and systems that measure success by completion rates rather than meaningful change. When we apply When we apply harm reduction with mandated clients thoughtfully with mandated populations, engagement improves because people feel heard rather than lectured. Legal compliance actually increases because participants develop genuine motivation rather than just going through motions. Long-term outcomes improve because change becomes internally driven rather than externally imposed.

Transforming the Counseling Experience

Even counselor satisfaction increases because the work feels more authentic and effective. There’s nothing better than having a person come in frustrated and annoyed about having to be there, and at the end of their first session hearing comments like “Thank you so much for listening” or “I finally feel heard.” They were always willing—the clinician just had to approach the client in a different way. When you see that shift happen in a single session, it reminds you why you got into this work in the first place. When you see the transformation in group dynamics and individual sessions, the difference is unmistakable.

Making the Language Shift

Getting started requires auditing your current approach. How often do you use phrases like “you need to” versus “the court requires” versus “what would be helpful for you?” Small language shifts can transform the entire dynamic. Expand your definition of harm to include legal, financial, relationship, and employment consequences in your risk assessment. Instead of monitoring court requirements as an outside observer, help clients develop systems to manage them independently. When you document your work, frame harm reduction with mandated clients in language that demonstrates progress toward court-mandated goals.

Free Resource: Month 1 Foundation Toolkit

Create your free account and find the Justice-Involved Treatment Mastery Series toolkit in the free resources section:

- Language Audit Quick Reference (what to say/avoid with mandated clients)

- Court Success Planning Template (the 4-step collaborative process)

- Documentation examples that satisfy courts while supporting harm reduction

This is the foundation of the complete Justice-Involved Treatment Toolkit you’ll build throughout this series. Each month adds new components to create a comprehensive resource system.

This is the first post in our Justice-Involved Treatment Mastery Series. If you missed last month’s foundation piece “From Compliance to Care: Why Justice-Involved Clients Need a Different Approach,” catch up here before diving into this series.

Next month: “When the Judge Says Abstinence but Evidence Says Harm Reduction” – where we’ll dive deeper into managing the tension between court requirements and clinical best practice.

What’s your biggest challenge when doing harm reduction with mandated clients? Share in the comments – your question might become next week’s focus.